William McKinley's Bicycle Bloc

The grassroots organizers and swing voters of the 1896 election.

For January, I’m releasing a multi-part series on the history of the bicycle. This is not a chronological history; rather, it’s a thematic one. Each entry explores one idea central to the development of the bicycle.

This is the final installation in the series. Past installations have covered tricycles, bloomers, the bike lane, and aluminum bike frames.

During election season, we hear a lot about different voting groups, each defined by their own characteristics and interests: the “NASCAR male,” the “lunch-pail Catholic,” the “Cuban millennial,” the “soccer mom.”

In the 1890s, it was all about the “bicycle bloc.”

At the end of the 19th century, millions of Americans owned bikes. And the 1896 election, a battle between Republican William McKinley and Democrat William Jennings Bryan, fell right in the middle of this bike craze.

At the heart of the 1890s American bicycle movement was the League of American Wheelmen. The League –– not affiliated with a particular political party –– worked solely to promote the interests of cyclists by encouraging bike-friendly legislation and fighting for good roads. In the 1890s, League had more than 70,000 members, which is why, in 1896, one Indianan wheelman declared:

“We are of such number that due consideration must be given to us on account of our votes and the influence we can exert in national politics.”

The bicyclists were influential swing voters –– up for grabs by whichever political party could best appeal to them.

And the Republicans wanted these votes, in part because the Republican National Committee (RNC) saw the cyclists as key to addressing one of the party’s main issues in the ‘96 election: Democrat William Jennings Bryan’s campaign tour across America.

Up to this election, politicians generally only traveled when necessary. It was hard to traverse the nation, and many Americans considered campaigning beneath the dignity of a high office candidate. But Bryan broke from this tradition, chartering a train and visiting more than half the states during his campaign.

McKinley, though, was of the traditional mindset. He told an aide during the campaign: “Don’t you remember that I announced that I would not under any circumstances go on a speech-making tour?” So, the Republican campaign approach was different: First, McKinley would give speeches from the porch of the Governor’s Mansion in Canton, Ohio, and second, the RNC would flood the country with Republican literature from posters to pamphlets to lapel buttons.

On both counts, the RNC realized bikers would be key.

On the first, cyclists could ride to Canton to attend the speeches. For instance, in October 1896 –– a month before the election –– several hundred wheelmen biked to Canton where McKinley spoke to them about cycling-relevant policies (good roads!) and was presented with a new bike (even though he wasn’t a cyclist).

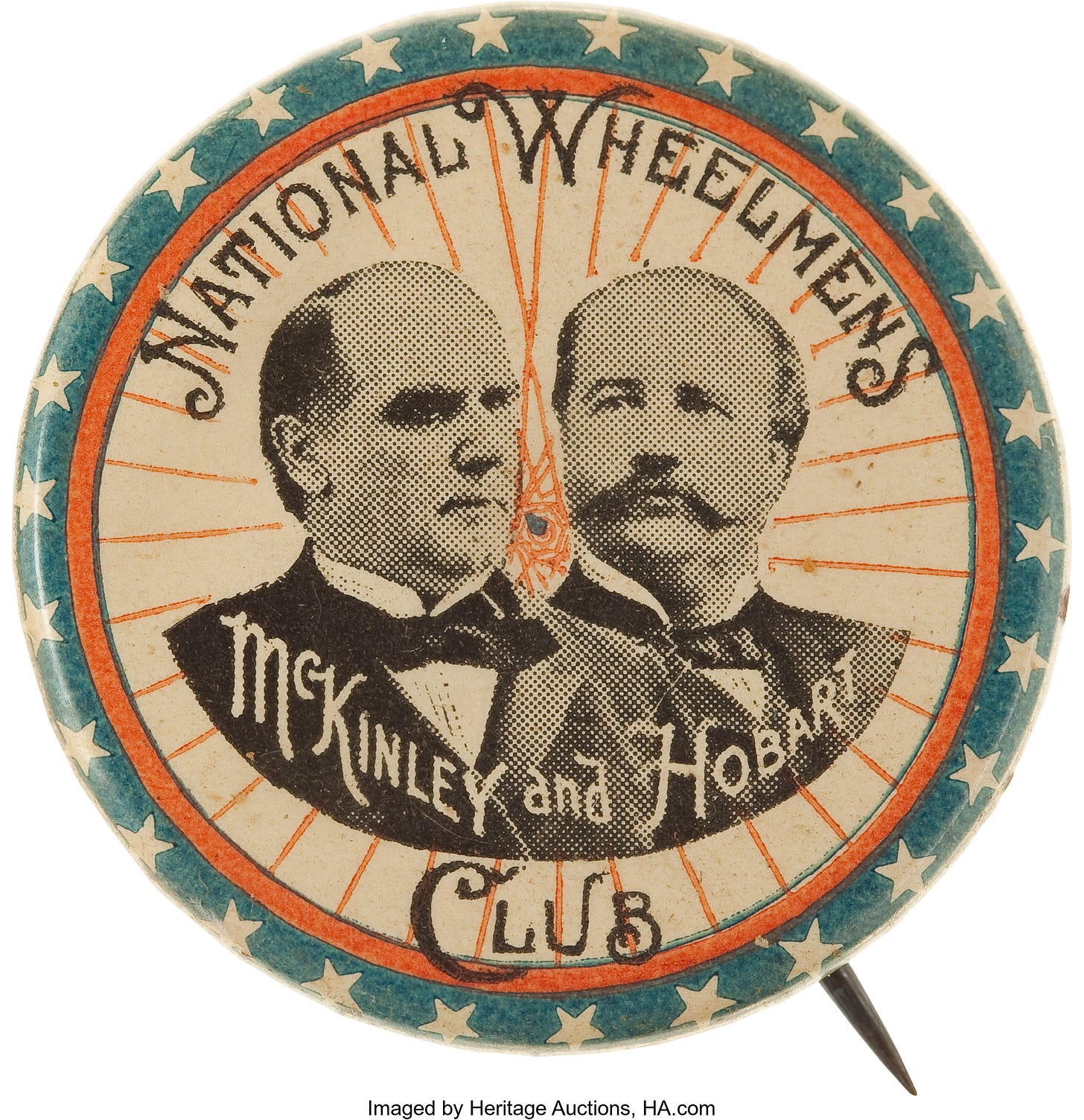

On the second, the RNC turned to cycling clubs. There were thousands of pre-existing cycling clubs across the country, and many club members were young businessmen whose interests already aligned with the Republican Party. The RNC capitalized on this by creating their own club in August 1896: the National Wheelmen’s McKinley and Hobart Club. The Chicago Tribune wrote: “The Republican leaders have recognized the wheel as an important factor, and look to the new organization to swell the hosts beneath the McKinley banner.” Thousands of members joined the central Chicago chapter, and dozens (maybe hundreds) of offshoots popped up in cities and towns across the US.

The clubs spread the Republican platform by cycling from town to town, attending and organizing rallies, and passing out pamphlets that promoted McKinley. For instance, on October 24, 1896, at least 3,000 cyclists held three separate parades in Chicago.

Unlike railroads, bicycles could reach rural areas. In Terre Haute, Indiana, the Republican bike club organized a parade with over a thousand cyclists in attendance, and in the days before the ‘96 election, two hundred wheelmen cycled to the small town of Menominee, Michigan, in the state’s upper peninsula to campaign for McKinley.

At all of these events, the clubs distributed McKinley promotional materials. That’s why Chicago GOP leader Chauncey Depew hailed cyclists as “one of the most active and most intelligent agencies in distributing … literature.”

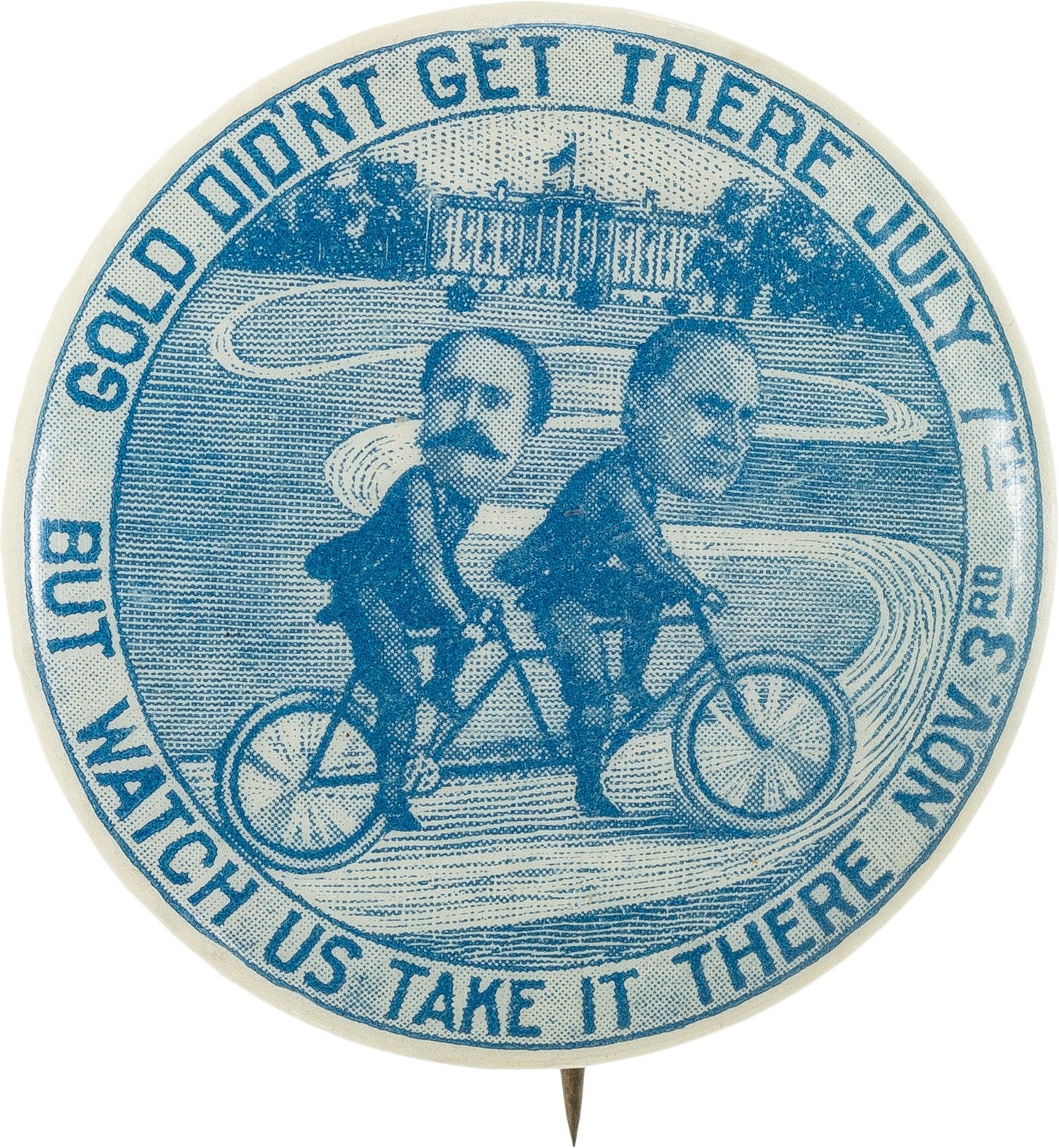

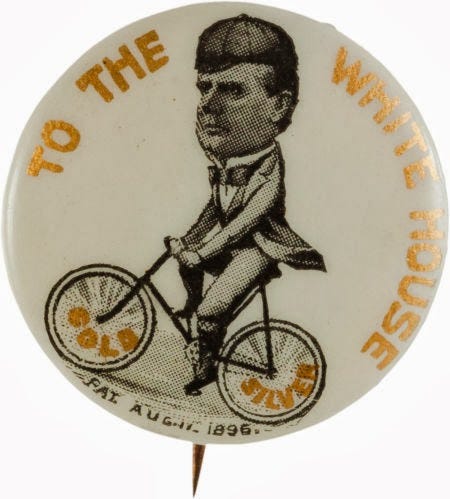

The RNC formalized their embrace of cyclists by adopting the bicycle as a campaign icon. The RNC produced lapel buttons with bicycle designs: a spry McKinley riding a bike to the White House, McKinley and VP candidate Hobart riding a tandem bike to the West Wing, and Uncle Sam at the handlebars with the slogan “Old Reliable G.O.P. Bicycle.” The bike became a symbol for the Republican party not only because of the cycling clubs but also because the bicycle stood for an honest, optimistic industry: The bicycle industry was one of the few that had grown during the 1893-96 depression, and the technology symbolized American progress and growth.

Sure, there were some cyclists for Bryan, but the Democrats struggled to win over the bikers. This was partly because Bryan’s sober, evangelical image clashed with the carefree spirit of the bicycle craze, but it was also for policy reasons: The Republican platform focused on economic recovery and stimulating American industry, including road improvements (which was in line with the cyclists’ interests in good roads).

McKinley won the election. While it’s hard to know how much of this is thanks to cycling, this 1890s bicycle bloc offers a glimpse into a time when technology spurred grassroots political involvement and activism.

Which sounds a bit like the technological world we’re living in today…

Notes.

This piece is excerpted and adapted from Michael Taylor’s article “The Bicycle Boom and the Bicycle Bloc: Cycling Politics in the 1890s” (Indiana Magazine of History, 2008).

The “Center Line Rule” blog has a three-part series on bicycling and the presidency, though it’s a little light on citations.

The voting groups at the top of this post are pulled from POLITICO research for the 2016 election.