For January, I’m releasing a multi-part series on the history of the bicycle. This is not a chronological history; rather, it’s a thematic one. Each entry explores one technology central to the development of the bicycle.

This is the second installation in that series. The first installation looked at the tricycle.

In 2020, the Poverty Action Lab published an article titled: “Can digital technology help create a more gender-equal society?” The article posits “yes,” outlining how digital finance technologies have enabled women in countries like Nepal and India to gain more independence. Through cash apps and online bank accounts, women in traditionally resource-poor communities can manage their own finances –– and, in turn, invest in their education, health, and careers.

Technology can be a tool for female empowerment. Today, we see this with cash apps. In Victorian England, we saw this with the bicycle.

In the late 1880s, our modern bicycle –– the safety bicycle, which has two same-sized wheels and a chain-drive transmission –– was invented. These innovations over the safety’s predecessor, the very tipsy penny-farthing bike, led to smoother riding and fewer accidents. And, in turn, bicycle popularity spiked; by the 1890s, millions of men and women on both sides of the Atlantic were riding bikes.

But, with more biking came more biking accidents. And, when women were involved in cycling accidents, their clothes were often to blame. In 1897, the Daily Mail wrote: “Two young ladies were riding side by side. It was very windy, and the skirt of one blew into the wheel of the other, where it got caught.” And, in the Daily Press in 1896: “I think she failed because she could not see the pedals, as the flapping skirt hid them from her view, and she had to fumble for them.”

Critics used these accidents to argue that women weren’t suited for cycling. The main cycling magazine of the 1890s, Cycling, wrote in 1896: “The majority of traffic accidents happen to lady cyclists, and … unless a lady possesses extraordinary nerve … the streets of London are no place for her to indulge in cycling.”

But at the root of the issue was the garment, not the user. Victorian fashion standards expected women to wear large crinolines (stiff petticoats), bustles (padded undergarments), and corsets. These outfits were not conducive to cycling; they would limit mobility and get trapped in gears and wheels. Thus, for women to ride safely, they needed to dress differently.

In the late 19th century, a clothing revolution was underway: The Rational Dress Movement. Fighting for an emancipation from the “dictates of fashion,” Rational Dress advocates called for fewer layers and lighter fabrics to allow for more athletic activity. They promoted wearing bloomers (short full trousers), looser corsets (or no corset at all), and shorter (or no) skirts.

And cycling was the perfect use case for rational dress. It’s much easier to ride on a bike in bloomers than in a large skirt. Thus, cycling women were some of the first to embrace (and most vocally advocate for) rational dress.

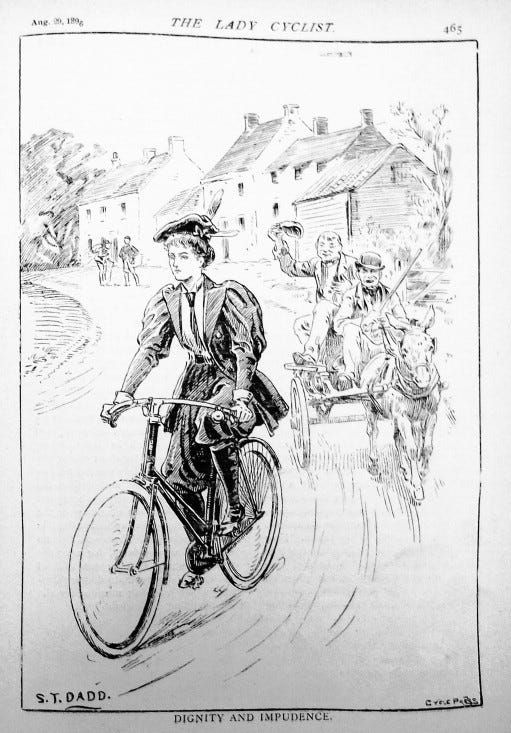

However, while these rational outfits were safer for cycling, they were subject to ridicule because they challenged Victorian fashion norms. Men would hurl insults (or even stones) at bloomer-wearing female bicyclists. The cartoon below –– published in The Lady Cyclist in 1896 –– captures this harassment, where impudent men are seen jeering at a dignified female cyclist.

Therefore, Victorian women sought clothes that would both be practical and respectable. But few of these existed, so women designed, patented, and sold new outfits. For example:

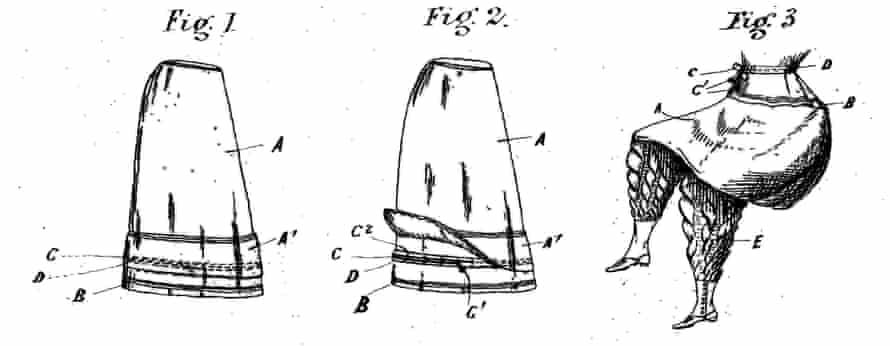

In 1895, dressmaker Julia Gill designed a convertible skirt that bunches up at the waist via hidden rings and cord into a “semi-skirt.”

In 1895, Alice Bygrave patented a skirt that used a series of pulleys to adjust the height of the skirt for any use. It was a hit and sold throughout America and the UK.

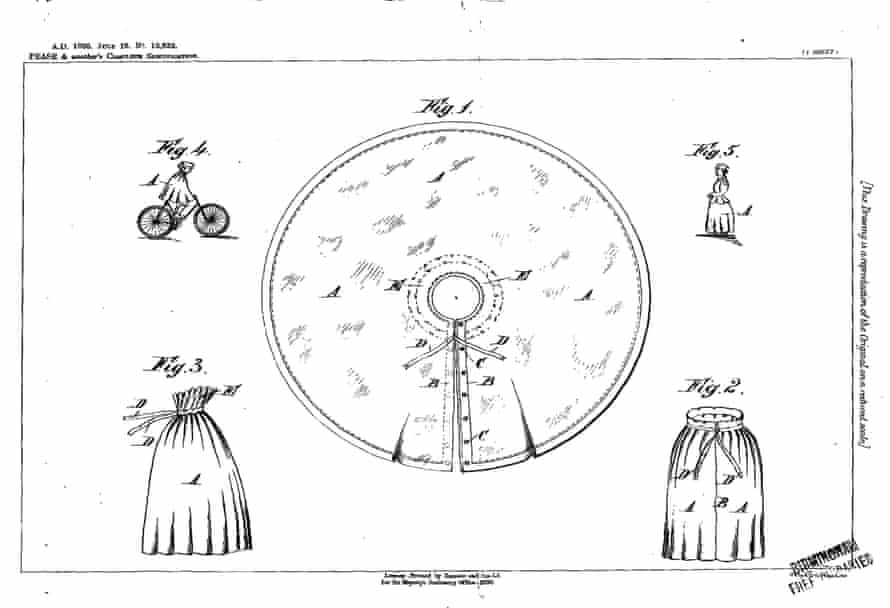

And, in 1896, Mary and Sarah Pease patented a removable skirt. When the user went for a bike ride, they would remove the skirt and wear it as a cape.

These outfits highlight how women creatively responded to the joint demands of cycling and Victorian gender norms. Patenting these designs was a political act, a statement about women getting to choose what activities they can participate in and what they can look like while doing these activities. In turn, these outfits –– by women, for women –– helped redefine female identity in Victorian England.

Long before women had the right to vote, the bike enabled women to extend their sphere of influence. Just like the digital cash apps of today, bicycles and bloomers in Victorian England were tools for empowerment.

Notes:

This post is based largely on research conducted by Kat Jungnickel (Goldsmiths College, University of London) on rational dress and cycling in late 1800s Britain. You can read Jungnickel’s research in this academic paper or in this Guardian article.

Other sources include:

“Progress and Flight: An Interpretation of the American Cycle Craze of the 1890s” (Richard Harmond, Journal of Social History, 1972)

“Cycling Accidents and 1890s Moral Panic” (The Victorian Cyclist, 2015)

“How Cycling Clothing Opened Doors for Women” (Christine Ro, The Atlantic, 2018)

“Fashion, Emancipation, Reform and the Rational Undergarment” (Deborah Warner, Dress, 1978)

The Wikipedia page on biking and feminism

You can download sewing patterns based on the innovative cycling outfits, through Kat Jungnickel’s Bikes and Bloomers project.

Jeffrey, I just want to say that I am loving this series and excited about anything else you're going to cover in The Curiosity Cabinet!!