This piece is written by Tim Miller.

Tim is a Boston-based cycling enthusiast, who studied materials science and economics at Penn and is currently pursuing an MBA at MIT Sloan. If not out on his bike, he is probably listening to a cycling podcast, watching professional racing highlight videos, or planning his next ride. His love of cycling grew out of a sense for adventure as well as rides with his mother around the suburbs of New Jersey and the long flat roads of the Jersey shore.

For January, we’re releasing a multi-part series on the history of the bicycle. This is not a chronological history; rather, it’s a thematic one. Each entry explores one idea central to the development of the bicycle.

Past installations have covered tricycles, bloomers, and the bike lane.

Buying a Bike.

I was shopping for a new bike recently. The process left me overwhelmed and confused: From color, to brand, to ride style, to type of wheels, there are countless options.1 But, above all, the most important selection is the frame. It determines overall ride quality… and price.

The four most common frame materials are steel, titanium, aluminum, and carbon fiber. Each optimizes for some combination of weight, durability, and price.2 Specifically, people want frames with a high strength-to-weight ratio –– a strong bike that does not weigh too much. (A low price is also nice!)

Forty years ago, steel frames were most common. Today, it’s aluminum. Carbon fiber –– the lightest and most expensive –– is reserved for high end bikes and on the roads of the Tour de France.

Now, I could write 10,000 words on the geometry, aerodynamics, mechanical properties of bike frames, but I stopped short out of fear of putting you to sleep.3 So, let’s focus on the most curious of frame materials: Aluminum, a somewhat tragic character in the history of bicycle innovation.

The Early Days.

Because of its high strength-to-weight ratio, relative abundance, and resistance to corrosion, aluminum has always been an important option for bike frames.

Aluminum bike frames were first produced in the 1890s. At the time, the most popular aluminum frame model was the Lu-Mi-Num, manufactured by St. Louis Refrigerator & Gutter Co. in the United States. According to a 1942 Cycling Weekly article, the Lu-Mi-Num did not rust “the frame, being polished to a mild degree of brilliance” and was light, but not “markedly lighter than other high-grade makes of the period.”

However, manufacturing a Lu-Mi-Num bike was costly and complex because the bike was made from a single casting. Single casting allowed the Lu-Mi-Num to avoid lugs (socket-like sleeves) in the construction process, especially important because –– while aluminum is strong –– it is a soft metal and does not lend itself well to welding.

The aluminum frame fell further out of favor in the 1940s because, as World War II started, aluminum became rare on the consumer market, with most supplies reserved for the war effort.

Thus, the early 20th century aluminum frame was short-lived. Manufacturers instead opted for a simpler, cheaper steel frame, which would become the top choice for decades.

That said, some aluminum frames were still available, and the frame did have vocal advocates in the cycling community. To quote a 1942 article in Cycling Weekly:

“Rumours [sic] are rife in the inner circles of the cycling world and behind the scenes in the cycle trade – concerning the likelihood of aluminium [sic] being more widely used in the construction of bicycles.”

Unfortunately, the article was ahead of his time: It would take nearly 40 more years for this prediction to come true.

A Turning Point… and Some Litigation.

In the late 20th century, during the US biking boom, aluminum frames finally started to take off. Advancements in materials (namely special aluminum alloys), frame designs, and manufacturing processes helped solve the biggest issues plaguing the mass production of aluminum frames.

While French brand Vitus and Italian brand Alan had been producing aluminum frames in the 1970s, the industry hit a turning point in 1983 when American-based Cannondale introduced the FT500 aluminum touring bike. The FT500 launched aluminum frames into the mainstream. Other companies followed Cannondale, and soon, there were lighter aluminum bikes for both entry-level cyclists and professional racers.

However, litigation nearly stopped this success story. After releasing the FT500, Cannondale was sued by Gary Klein (of Klein Bicycle Corporation) for intellectual property infringement. Klein claimed Cannondale copied his patented designs, which he had first developed as an MIT undergraduate.

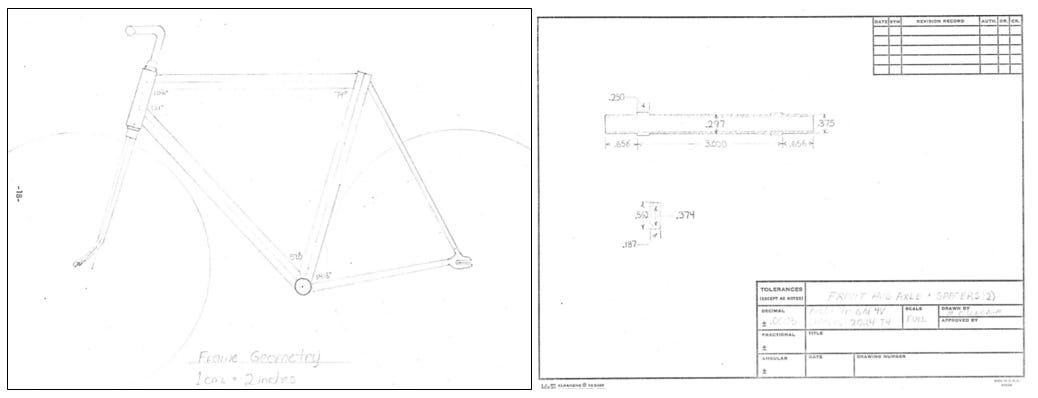

But Klein’s patents actually referenced designs developed by two other MIT students –– Marc Rosenbaum and Harriet Fell –– in 1974.4 5 Given these references to “prior art” in the patent, Cannondale claimed Klein had no basis for the suit.

The courts ruled in Cannondale’s favor, paving the way for the company to spread the gospel of the aluminum frame. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, aluminum unseated steel as the go-to material for bikes, both on the professional cycling tour and amongst the masses.

Make Way for Carbon.

However, aluminum’s position as the preeminent bike frame material was short-lived. Always looking for the next best thing, manufacturers started experimenting with a new material: carbon fiber. Although expensive, carbon fiber’s high strength-to-weight ratio made it ideal for a bike frame. Throughout the 1990s, carbon fiber replaced aluminum as the material of choice for pro-cyclists and high-end bikes. Aluminum was designated for mid and entry level bikes.

The Current State.

After a long and bumpy road –– fending off manufacturing problems, world wars, and advanced composites –– aluminum has proven itself a worthy bike frame material. Most of the bikes you see out on the road are made of aluminum. It has even started to make a comeback in the high end road bikes, pulling back some market share from carbon frames.

While writing this article article, I’ve come to appreciate the beauty and innovation of bike design and manufacturing, but I am still overwhelmed with the decision on which bike to get.

I guess I have to buy one with an aluminum frame, right?

Are you interested in writing a column for The Curiosity Cabinet? Reply to this email with any ideas you have!

Notes.

“Why Carbon Bikes are Failing” (Eric Barton, Outside, 2018)

“First ever aluminum bicycle. Lu-Mi-Num ???” (Bike Forums discussion board)

“'Aluminium bikes are the future'... in 1942” (Nigel Wynn, Cycling Weekly, 2016)

“The Art of Bicycles” (Gary Klein, Speech Transcript, 2006)

“Aluminum Frames Are Back—And Better than Ever” (Joe Lindsey, Bicycling, 2013)

“M.I.T. Aluminum Bicycle Project 1974” (Harriet Fell & Marc Rosenbaum, sheldonbrown.com, 2016)

“Light Touch Puts LeMond in the Frame” (Elliott Almond, Los Angeles Times Online Archive, 1991)

“The return of the aluminum frame” (Mike Hawkins, Cyclist, 2015)

Non-sequitur: Over the last two years I have found myself biking a lot and naturally started telling everyone about my new hobby. In one of these conversations, after explaining some of my adventures, I was asked if I have bad gas. Initially taken back by such a forward question, I was told it is an acronym for Gear Acquisition Syndrome: the impulse to acquire new, and largely unnecessary, cycling gear, clothes, and accessories. I can confirm I have gas.

A saying in bike manufacturing: bike frames can be lightweight, durable, or cheap - pick two.

Plus, my editor (Jeffrey) put me on a strict word count, like a baseball manager does to a starting pitcher.

There is some inconsistency from primary accounts. Marc Rosenbaum and Harriet Fell say the bicycling building class took place in 1974, while Gary Klein says it took place in 1973.

I highly recommend reading more about the Aluminum Bicycle Project at MIT.