For January, I’m launching a multi-part series on the history of the bicycle. This is not a chronological history; rather, it’s a thematic history. Each entry explores one technology central to the development of the bicycle. This is the first installation in that series.

In June 1881, Queen Victoria was touring the Isle of Wight. Suddenly, a young woman –– amid a flash of spinning wheels –– zoomed by the Queen’s carriage. The Queen couldn’t catch up, so she sent her servants to track down this young woman.

The young woman was Ms. Roach, the daughter of a local tricycle salesman who was encouraged (for promotional reasons) to ride her trike around town. At the royal mansion, Roach demonstrated her tricycle for the Queen. Victoria was sold and ordered two immediately.

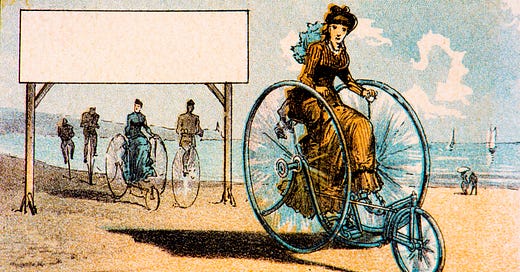

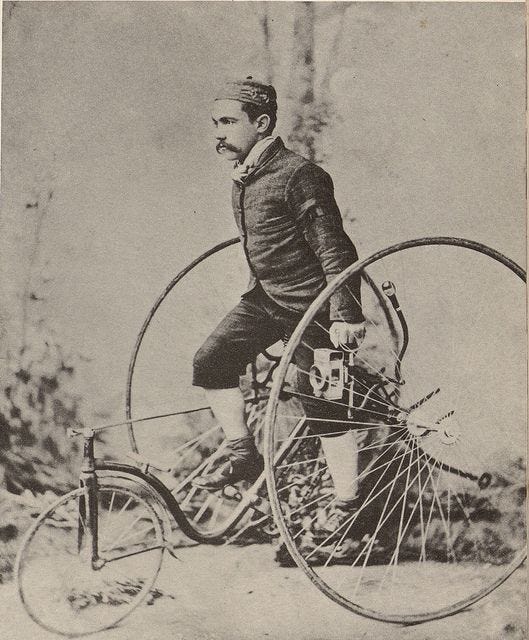

The tricycle’s popularity took off in the 1870s. At this time, the bicycle created a market for human-propelled transportation vehicles. But, the bicycle of the 1870s –– the Ordinary Bicycle (seen above) –– had a major problem. It had a very large front wheel and a very small back wheel, which made the vehicle really difficult to balance upon. Accidents were frequent, and the Ordinary Bicycle was seen as unsafe.

Thus, the stable tricycle was seen as a solution to the Ordinary Bicycle’s biggest issue: Staying upright.

The 19th century popularity of the tricycle was also driven by Queen Victoria’s endorsement. Thanks to the Queen, the tricycle was a hot commodity amongst the upper class. According to some accounts, every royal head of state had a fleet of tricycles. British Lord Albemarle described a time when:

“The Maharajah of an Indian state, together with the British resident at his court and all the greater officers of the durbah, [were] seated on tricycles at the gate of the palace.”

Because of their elite affiliations, tricyclists saw themselves as better than bicyclists. The Tricyclists’ Association sought special privileges in London parks, and the British Tricycle Union wrote about how they wanted to distance themselves from the bicyclists, “who are a disgrace to the pastime, while Tricycling includes Princes, Princesses, Dukes, Earls, etc.”

Thus, in the 1880s and 1890s, the tricycle was perceived as a viable alternative to the bicycle. The Evening Standard newspaper was distributed by tricycle. The British Post Office used tricycles to deliver packages. And, one 1886 catalogue of British cycles included 89 different bicycles and 106 different tricycles. The tricycle gained widespread acceptance, and many thought it was only a matter of time until the trike drove the bike to extinction.

So, what happened? Why’d the tables turn against the tricycle?

Largely because of the trike’s own safety issues.

First, most tricycles had three tracks, where the bicycle only had one track (when going straight). Therefore, when riding a tricycle, it was difficult to avoid stones and holes… and there were many of those on 19th century roads.

Second, the tricycle did not have effective brakes. To stop the trike, the rider had to back-pedal, which was difficult when going downhill. Tricyclists trying to regain control over quickly-spinning pedals would often be lifted from their seats.

Third, sitting between two large wheels –– as most 1890s tricycle configurations required –– was safe and stable when rolling smoothly. But it was less safe during a crash. In those unfortunate circumstances, it was impossible to not get tangled up in the spokes of the large wheels.

Because of these safety issues, the tricycle was not a flawless solution to the Ordinary Bicycle. It’s ironic: The trike gained popularity because of its perceived safety solutions but lost its popularity because of real safety concerns.

In turn, the tricycle never cornered the cycle market, leaving room for alternative solutions to the Ordinary Bike. By the 1920s, advancements in bicycle design and safety took hold, fueling the bike’s popularity and driving the trike out of favor. The three-wheeled cycle was largely relegated to life as a children’s toy.

Notes.

This post is adapted from Wiebe Bijker’s Of Bicycles, Bakelites, and Bulbs: Toward a Theory of Sociotechnical Change (pages 54-60). Bijker’s book is an extended argument for the social construction of technology theory, using the development of the bicycle as a primary example. It’s dense but interesting.