Nestlé Baby Formula (Part 2)

How everyday citizens changed Nestlé's marketing practices in Africa

If you haven’t read Part 1 of the Nestlé Baby Formula story (which is about how Nestlé promoted infant formula in Africa), you can check it out here.

One translation of the report was published under the title “Nestlé Kills Babies.” Nestlé sued over this (and won), but by that point, the cat was already out of the bag: Nestlé was under fire for their baby formula marketing in developing nations.

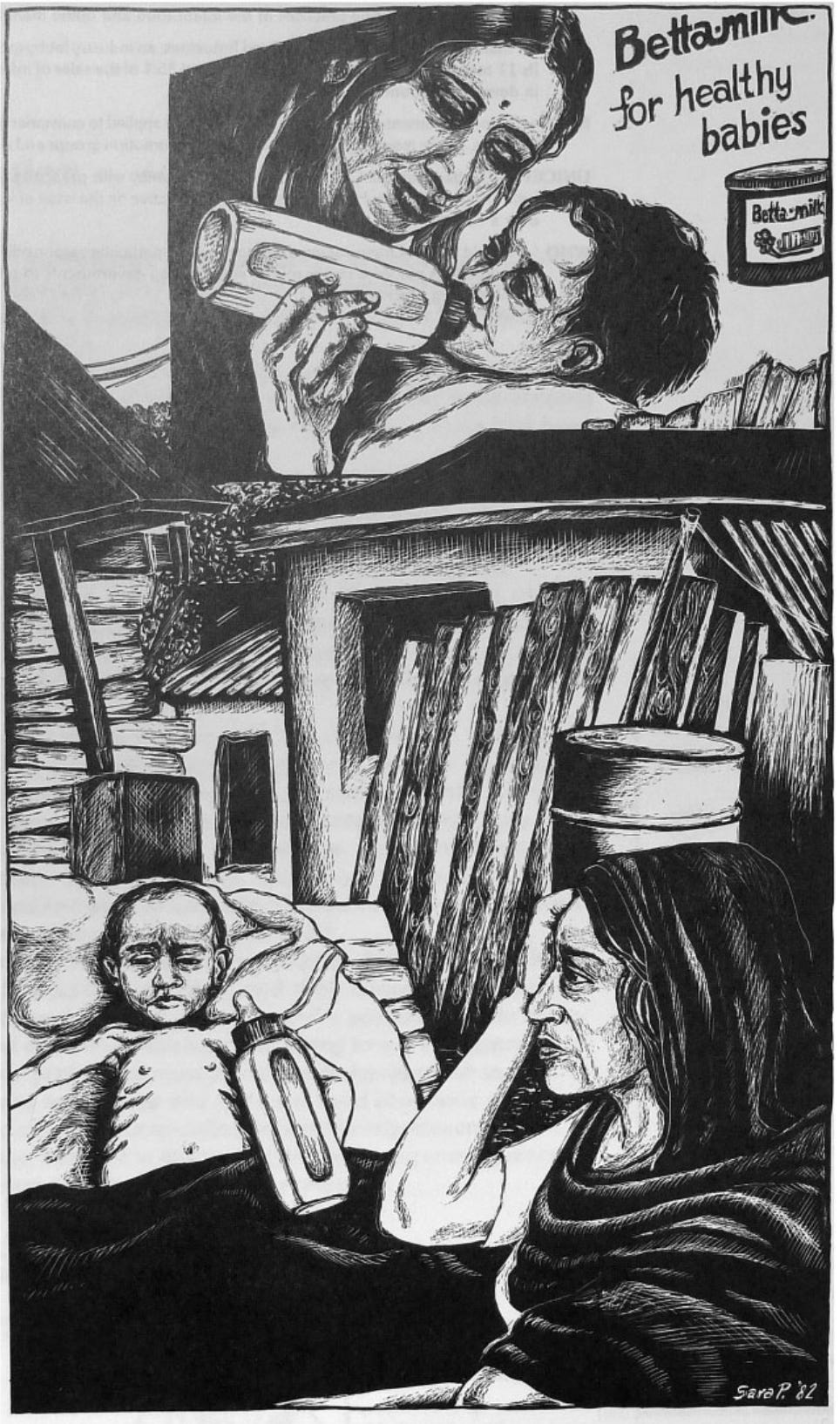

The report — originally titled “The Baby Killer” and published in March 1974 by the nonprofit War On Want — opened with the line: “Third World babies are dying because their mothers bottle feed them with western style infant milk.” The report argued that “more and more Third World mothers are turning to artificial foods during the first few months of their babies’ lives. In the squalor and poverty of the new cities of Africa, Asia and Latin America, the decision is often fatal.”

The rise of baby formula in the developing world started at the turn of the 20th century. Seeking new markets, Nestlé and other formula manufacturers began marketing their products in Africa. These corporate interests dovetailed with imperial interests from European-led governments in Africa, which were increasingly concerned with malnutrition among their colonial populations (largely because of its effects on labor and productivity). As a part of their marketing efforts, Nestlé both funded research on how formula could address malnutrition and partnered with medical officials to offer their product to mothers in Africa. Nestlé wanted their product to be seen as the “silver bullet” solution to malnutrition. (More on Nestlé’s promotional efforts in Africa in the first part of this two part series.)

However, by the mid-20th century, it was becoming clear this wasn’t the case. Enter “The Baby Killer” report, which laid out damning evidence against Nestlé’s promotion of infant formula.

Infant formula is a product of Western health ideals, centered around cleanliness and hygiene. However, it was difficult for mothers in Africa to access clean water and clean equipment to prepare formula. In turn, mothers in Africa would often prepare baby formula with non-potable water or using dirty equipment, making it almost inevitable that formula would introduce infection to babies. Nestlé, though, ignored these realities; in instruction manuals, they would tell mothers to boil water before mixing it with formula, even though these mothers often lacked the equipment to properly do so.

Further, formula was expensive. On average, a day’s feeding could cost up to one-half the average daily wages. In turn, parents would dilute formula to unsafe levels, so infants would not be getting enough nutrients in their daily diets.

And, once a baby was started on formula, it was often hard to go back to breast milk because lactation diminishes once a mother stops breastfeeding. Thus, mothers found themselves stuck on formula, even if they wanted to go back to breastmilk.

While critiques of bottle-feeding in the Third World didn’t gain attention until the 1970s, these concerns dated back at least four decades. After studying medicine at Oxford, Dr. Cicely Williams was trained in Malaya in 1939, where she discovered that mortality rates were higher among bottle-fed infants. She noted — just as “The Baby Killer” later did — that the economic conditions were to blame: Low-income mothers didn’t have the resources to use baby formula properly. At the time, Williams’ work stayed within a small community of experts, but in the 1970s, the War on Want campaign turned infant formula into an international scandal.

Though Nestlé was almost certainly aware of these issues, their marketing still promoted the idea that drinking formula, rather than breast milk, would make children healthier and stronger. “The Baby Killer” report argued that Nestlé deliberately misled potential customers. Ads offered free feeding bottles and samples to encourage mothers to purchase of formula. In turn, parents would become hooked on the product. (This free sample strategy is the same tactic Purdue Pharma employed to sell — and hook patients on — oxycontin in the US decades later.) According to United States Agency for International Development official Dr. Stephen Joseph, reliance on baby formula in Africa led to a million infant deaths every year through malnutrition and diarrheal diseases.

When the “Baby Killer” report was published, global concern surrounding consumer rights — influenced by folks like Ralph Nader — was on the rise. Governments and activists were placing increasing pressure on multinational corporations, including federal laws that regulated food quality and shareholder activism that aimed to restrict the growing power of these multinationals. Further, in the latter half of the 20th century, international development efforts were increasingly called into question; for the first time, NGOs accepted that so many of their development projects had negligible impact on the condition of the global poor. Into this milieu entered “The Baby Killer,” offering up the concrete example of baby formula as an issue grounded in both consumer rights and failed development efforts.

Because of the report, public pressure on Nestlé mounted. Advocacy groups around the world launched legal battles against formula makers to try to get them to change their marketing. In 1977 in the US, the Infant Formula Action Coalition (INFACT) launched a boycott against Nestlé, calling for global regulation of baby formula marketing strategies. The boycott started in Minneapolis (where Nestlé has its US headquarters), but it expanded nationally and then internationally. The campaign received support from ordinary women across the globe; by the end of 1977, INFACT was receiving 40 to 50 letters of support a week. Through consumer activism, INFACT used the global market to connect Western consumers to Third World mothers.

Initially, Nestlé tried to deny responsibility for deaths due to infant formula. For instance, in a 1978 hearing at the US Senate, Nestlé spokesperson Oswald Ballarin said the company was not responsible for deaths and illnesses because they had no control over the water supply: “We cannot have that responsibility, sir. … How can I be responsible for the water supply?”

However, succumbing to the public pressure in 1981, Nestlé agreed to a non-binding set of rules proposed by the World Health Organization. These rules regulated how infant formula could be marketed: Baby food companies could not promote products in hospitals or to the general public, give free samples to mothers, give gifts to health workers, or give misleading information. Esther Peterson, an advisor to Presidents Johnson and Carter, called this agreement “the most important victory in the history of the international consumer movement.”

The generally accepted narrative is that the boycott served as the culmination of decades of medical warnings against Nestlé. However, it wasn’t that simple. Right before the boycott, Nestlé was seen as an upstanding company. The corporation was known for working closely with doctors and NGOs to promote infant health and combat infant protein deficiency. This public perception changed on a dime — thanks to one report and an international boycott. The giant fell from compassionate corporation to bad business.

Notes.

Sources, listed in order of use:

“Milking the Third World? Humanitarianism, Capitalism, and the Moral Economy of the Nestlé Boycott” (Tehila Sasson, American Historical Review, October 2016)

“The Controversy over Infant Formula” (Stephen Solomon, New York Times, 6 December 1981)

“Nestlé’s Corporate Reputation and the Long History of Infant Formula” (Lola Wilhelm, Oxford Centre for Global History’s Global History of Capitalism Project, November 2019)

“Every Parent Should Know The Scandalous History of Infant Formula” (Jill Krasny, Business Insider, 25 June 2012)

Other sources: 1977 Nestlé Boycott, Professionalism and the Nestlé infant formula scandal

Part 1 can be found here.

The parenthetical comment on oxycontin is drawn from Patrick Radden Keefe’s Empire of Pain, which I’m currently reading and very much endorse. There are certainly some interesting parallels between oxycontin in the US and baby formula in Africa…