Nestlé Baby Formula

Imperialism, nutrition, and the promotion of Nestlé's infant formula in 1950s Africa

Baby formula has always sat at the nexus of business and government.

Infant formulas first became popular in the Industrial Revolution. With more women entering the workforce, artificial baby formulas became an easy way to feed infants while mothers were away at work.

The medical and scientific establishment supported the use of baby formula, endorsing the product as a pure and safe option to feed a growing baby.

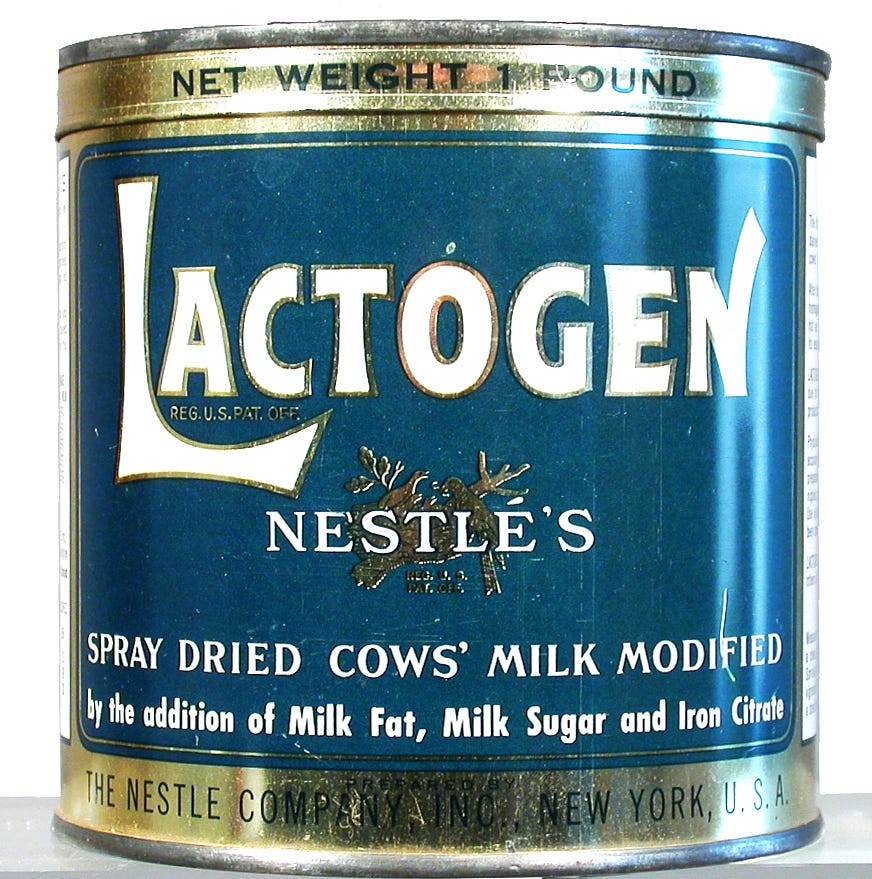

From this backdrop, in 1866, the company Nestlé arose. Based in Switzerland, the corporation manufactured a powdered infant-feeding formula, which –– at least per the 1870s recipe –– was based on ground bread and a sweetened condensed milk paste. It was known for being rich in protein and key nutrients for infants.

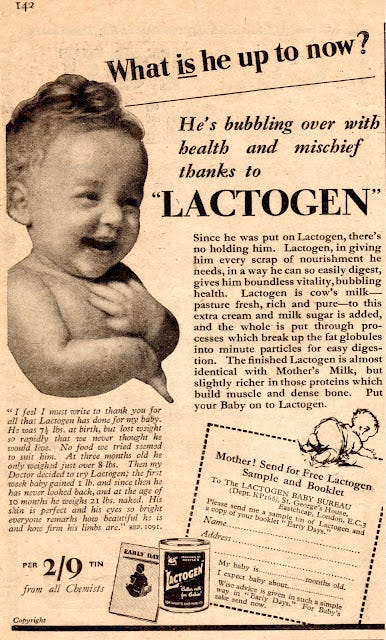

Nestlé’s core marketing strategy relied on this feature of the product: The company wanted to be the healthy, nutritious, doctor-approved baby formula. To develop this reputation, Nestlé nurtured close alliances with researchers and physicians. To promote the product around Europe, the company partnered with doctors who would serve as spokespeople and conduct clinical trials supporting Nestlé’s health benefits. These positive reports were turned into company advertisements, bolstering the Nestlé brand as “scientifically-endorsed.” Nestlé wanted mothers to see their baby formula as a better, more healthful option than both alternative formulas and breastmilk (even if this wasn’t necessarily true).

It was this “scientifically-endorsed” reputation that thrust Nestlé into the center of imperialism efforts in post World War II Africa. At the time, Nestlé was looking for ways to grow sales, and Africa proved to be a prime new market for baby food.

Until the 1920s, European knowledge of nutrition in Africa was slim, but in the 1930s, this changed as infant nutrition became an increasingly important instrument of imperial power. Imperialist concerns over colonial nutrition stemmed from concerns over declining labor productivity and fertility rates, which European governments viewed as a threat to their colonial profitability. In other words, nutrition was seen as a way for Europeans to maintain an exploitative power over Africans.

At the crux of this was the disease “kwashiorkor,” the Ghanian word for “protein deficiency.” The disease –– first described in the 1930s –– sat at the center of nutrition agendas for many European NGOs (e.g., the World Health Organization, UNICEF). Researchers thought the disease originated in babies around the time of weaning, when children transitioned from breastmilk to the protein-poor diet of the family.

The recommended treatment for the disease was rather simple: A diet rich in proteins. Often, this was powdered skim milk, but some pediatricians insisted on more than this, promoting a “complex mineral therapy.” In other words, baby formula –– which was high in protein –– was the ideal treatment.

Further, colonial officials observed that African mothers breastfed newborns for longer than their European counterparts. These European officials saw this as a problem because native traditions often prevented sex during breastfeeding, which led to more birth spacing and, in turn, a lower fertility rate among African women. Europeans, at least in part, attributed their colonial labor shortage to this tradition of extended breastfeeding, so by promoting baby formula, they hoped to increase colonial fertility rates.

Thus, European-backed health institutions rallied behind baby formula as the key to a healthy, plentiful workforce.

Nestlé saw and seized the opportunity. In the 1950s, Nestlé sent medical delegates to Africa to connect with colonial physicians, conduct clinical trials, and promote their products as a treatment to malnutrition. For instance, in 1956, one Nestlé medical rep embarked on a six week tour of French African territories, which included visiting 112 doctors, 60 hospitals, 50 pharmacists, and organizing 40 clinical experiments. In one of Nestlé’s Africa-based clinical trials (conducted in 1954), a pediatrician at a hospital in Senegal found that –– when Nestlé products were given to young children –– biological syndrome improved and mortality rates decreased from 80% to 25%.

Nestlé promoted these results (and others like them) not only in advertisements distributed across Africa but also among the colonial medical community. They presented their findings at the inter-imperial association conference and published them in French and English medical journals. They were brand building, legitimizing Nestlé as a medical solution to malnutrition in the colonies.

This strategy worked. By the second half of the 1950s, Nestlé reported increased sales across the African continent.

Because, from the 1930s to the 1950s, imperial interests created a colonial context in which nutrition science –– particularly malnutrition theories like those surrounding kwashiorkor –– thrived. Government initiatives to address nutrition created new opportunities for corporate growth, which businesses like Nestlé seized.

Nestlé’s success lasted until the 1970s, when a bombshell report exposed the true and troubling consequences of their promotion efforts in Africa… but more on that next time.

Notes.

The above post is largely adapted from Lola Wilhelm’s article “‘One of the Most Urgent Problems to Solve’: Malnutrition, Trans-Imperial Nutrition Science, and Nestlé's Medical Pursuits in Late Colonial Africa” (The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 2020).

Other sources include:

“Mechanical milk: An essay on the social history of infant formula” by Michael Schwab (Childhood, 1996)

“Nestlé’s Corporate Reputation and the Long History of Infant Formula,” which is a 2019 case study for Oxford’s Global History of Capitalism Project (written by Lola Wilhelm, Oenone Kubie, and Christopher McKenna)