Whenever I teach environmental science, I use one sentence as a guiding principle: “The Earth is an interconnected system.” My students come to know this phrase so well that it becomes a call-and-repeat game. “The Earth is…,” I’ll say. “An interconnected system!” they’ll shout in response.

The idea is simple: Nothing on our planet sits in isolation –– there are webs, networks, and consequences tying everything together, even if we might not see it. Take whale poop as an example.

Let’s start with an obvious fact: Whales are big.

When a whale eats, it feeds on tiny animals (krill) in the water column. And, because whales are big, they are moving up and down through the ocean. They are also eating quite a lot as they traverse the water column. For about 120 days straight, a blue whale eats 8,000 pounds of krill a day. That’s almost 500 tons of food. In other words, whales eat a lot.

And for my second obvious fact: Whales poop.

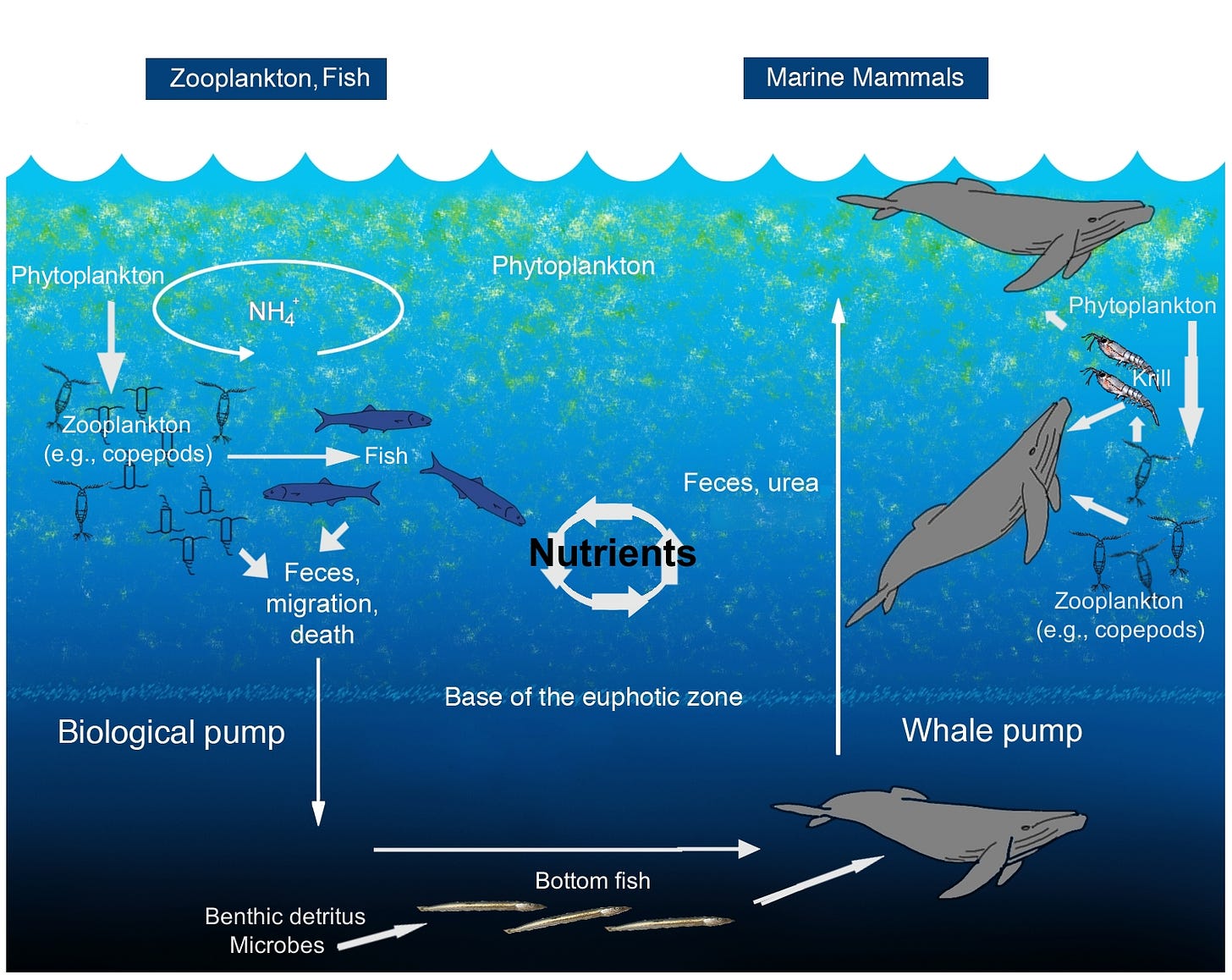

While whales eat food throughout the entire water column, they only defecate when breathing at the ocean’s surface. In turn, in a process scientists call “the whale pump,” whales take the organic matter they collect throughout the ocean and deposit it at the surface in buoyant fecal plumes (poop). These plumes are rich in nutrients, such as iron. The iron concentration in whale fecal plumes is at least 10 million times greater than ambient levels.

This is where the climate-altering power of whale poop comes into play. Phytoplankton –– tiny, photosynthesizing algae –– need iron to grow, but the nutrient is often hard to come by in the surface ocean. Therefore, a whale fecal plume is an iron field day for phytoplankton. The plume fertilizes the surface ocean, promoting phytoplankton growth. These phytoplankton then photosynthesize, which involves removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and converting it into sugars.

Eventually, these little algae will die, and when they die and sink down to the bottom of the ocean, they take the carbon in their bodies with them. Thus, the phytoplankton remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and bury it deep in the ocean.

Because carbon dioxide is a greenhouse gas that contributes to climate change, whales can stop climate change –– all because of their poop.

The scale of this effect is surprisingly large. If we consider just the whale’s fertilization of the ocean, one study in the Gulf of Maine found that whale fecal plumes add more nitrogen –– another important plant nutrient –– to the surface ocean than all rivers entering the Gulf combined.

Now, consider the atmospheric effects of the whale pump. A study published in August 2020 estimates that the current global whale population of ~1.3 million stimulates the burial of 370 million tons of carbon dioxide each year through this poop fertilization. In other words, that’s 740 billion pounds of carbon dioxide removed from the atmosphere because of whale poop.

This effect used to be much larger. Before industrial whaling, there were close to five million whales in our oceans. Thus, the whale pump used to be nearly four times stronger than it is today. Imagine all the plumes, all the algae, all the buried carbon.

In turn, some scientists argue that bringing back whale populations to pre-whaling levels is one key to stopping climate change. Of course, whales aren’t the only solution to climate change –– responding to our climate crisis requires broader considerations than just the whale pump. But actions have consequences. Whaling affected the climate. Because the Earth is an interconnected system.

One small change can have massive effects on the entire system. Some people might call this the butterfly effect, but I call this the whale poop effect.

Notes:

A lot of the research on the whale pump was pioneered by Joe Roman at the University of Vermont. His paper on whales as ecosystem engineers –– which discussed the whale pump and much more –– can be found here. It’s a great read.

Roman’s first paper on the whale pump and nitrogen cycling in the Gulf of Maine can be found here.

Andrew Pershing at the Gulf of Maine Research Institute explores whale carcasses as a vehicle for carbon sequestration here.

This magazine article offers an interesting argument for why saving whales could be a key to fighting climate change.

Science journalist Ferris Jabr wrote a nice Twitter thread on whales and climate.