Victorian Christmas Cards

On the holiday's absurd and macabre symbolism in 19th century England

These days, Christmas cards are tame. Maybe there’s a family photo. Maybe there’s a sketch of Santa Claus or a snowman.

This wasn’t the case in 19th century England, when Christmas cards first came to prominence in English society. The first commercial Christmas card (shown below) was printed in 1843, featuring a design of a family by painter John Calcott Horsley. The cards were lithographed and hand colored, with 1,000 produced and sold for a shilling each, an entire day’s earnings for a worker at the time.

Over the coming decades, the Christmas card became a fixture of the holiday in Victorian England. Their rise in popularity was due to both a changing postal system and new printing technologies. In 1870, the British government introduced halfpenny postage, making sending letters affordable and accessible for everyday citizens, and at the same time, the industrialization of color printing — specifically die-cutting and chromolithography — allowed for the mass production of cards. The Christmas card industry took off: By 1880, over 11 million Christmas cards were produced annually in Britain alone.

This new technology, coupled with the commercial drive to create cards that grabbed consumers’ attention, led to a diversity of colorful, intricate, and creative designs. According to Zorian Clayton, curator of prints at the Victoria & Albert Museum, the quest for “novelty and surprise” led to cards that “just got more and more weird and wonderful.” There were so many designs introduced each year that newspapers would run reviews of the season’s designs — a “best of” list, if you will.

According to the York Museums Trust, Victorians valued the quality of the image often more than the subject — as a testament to the printing quality and technical skill of the machines — which led to surprisingly intricate designs.

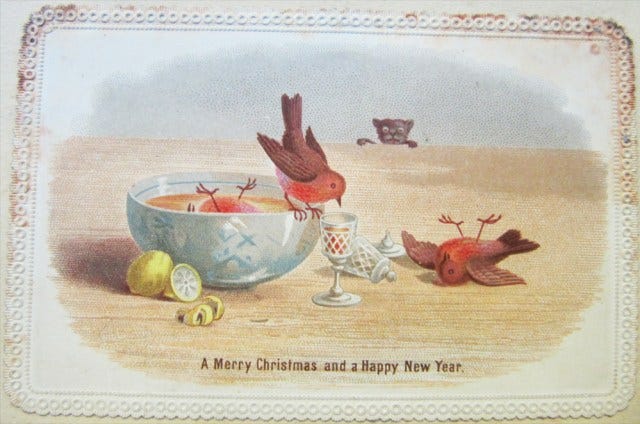

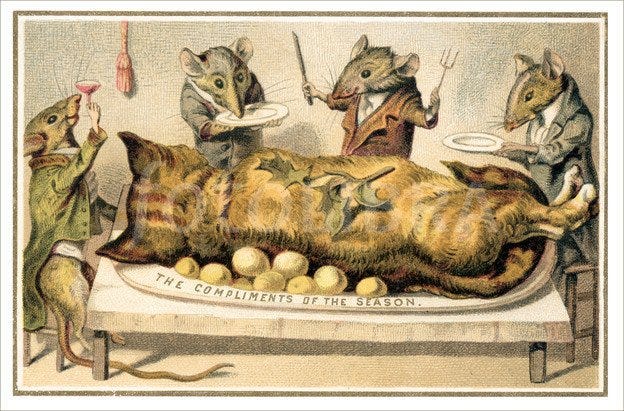

A lot of these cards were dark in theme. Violence was common. Clayton explains: “It was a much crueler world. With the kinds of things you would have seen on the streets in Victorian London, you would have been much more hardened. Their humor is definitely at odds with some of the stuffiness we imagine.” Pests like rats and roaches were frequently depicted, even though they were seen as nuisances. Above, rats feast on a cat; below, a frog murders another frog… for money.

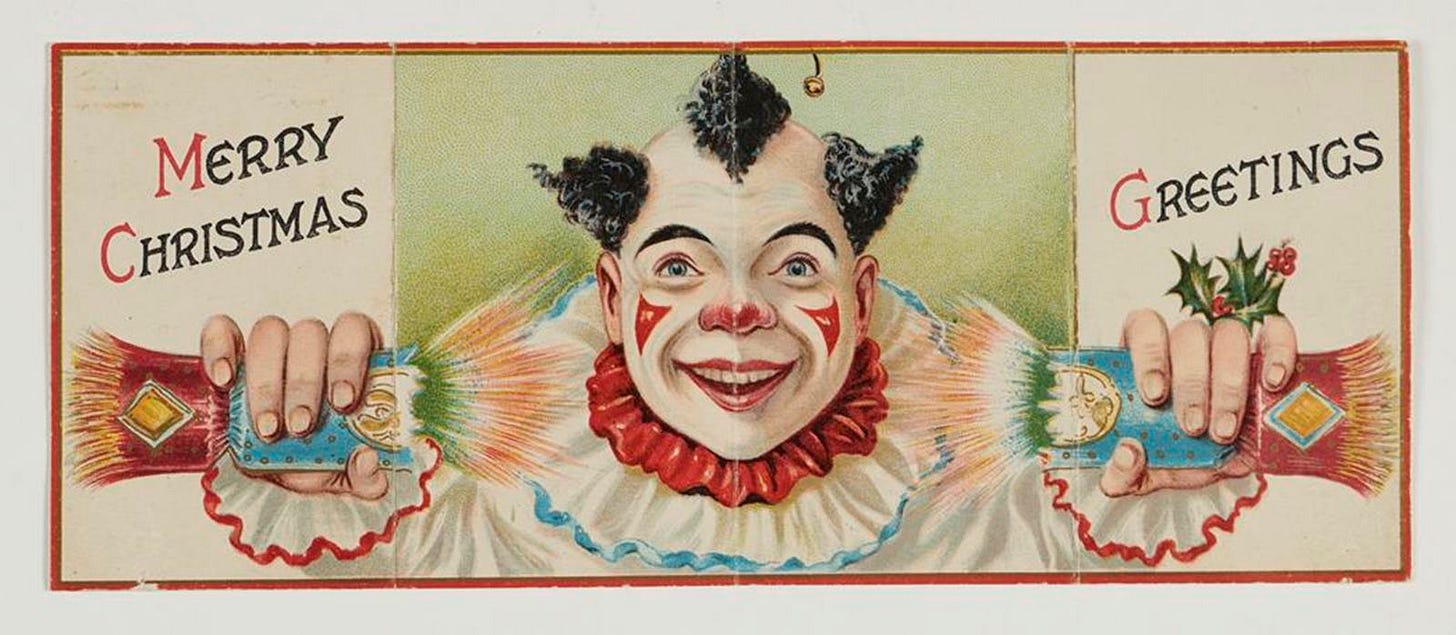

And here a clown terrorizes both a goose and a police officer:

According to author Arthur Blair: “As the novelty of snow scenes, holly and robins became commonplace, [more unconventional and humorous designs arose, such as] unfortunate men falling through the ice, clowns knocking down policemen and other such happenings that often raise unsympathetic laughter from the onlooker but never the victim.” These designs attempted to grab consumer attention by stepping outside of the norm. Perhaps, in some cases, too far outside of the norm.

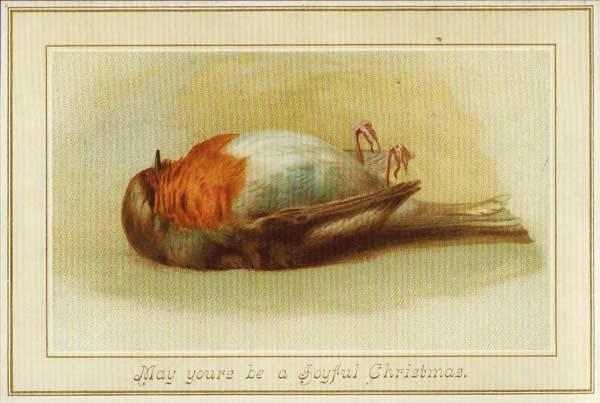

Death was common on these cards. For instance, many Victorian Christmas cards featured a dead robin. Today, we’d probably see this as unpleasant, but in the Victorian period, a dead bird was a symbol of good luck. It represented how on St. Stephen’s Day (the day after Christmas) people would often kill a robin or a wren to bring forth good fortune in the year ahead.

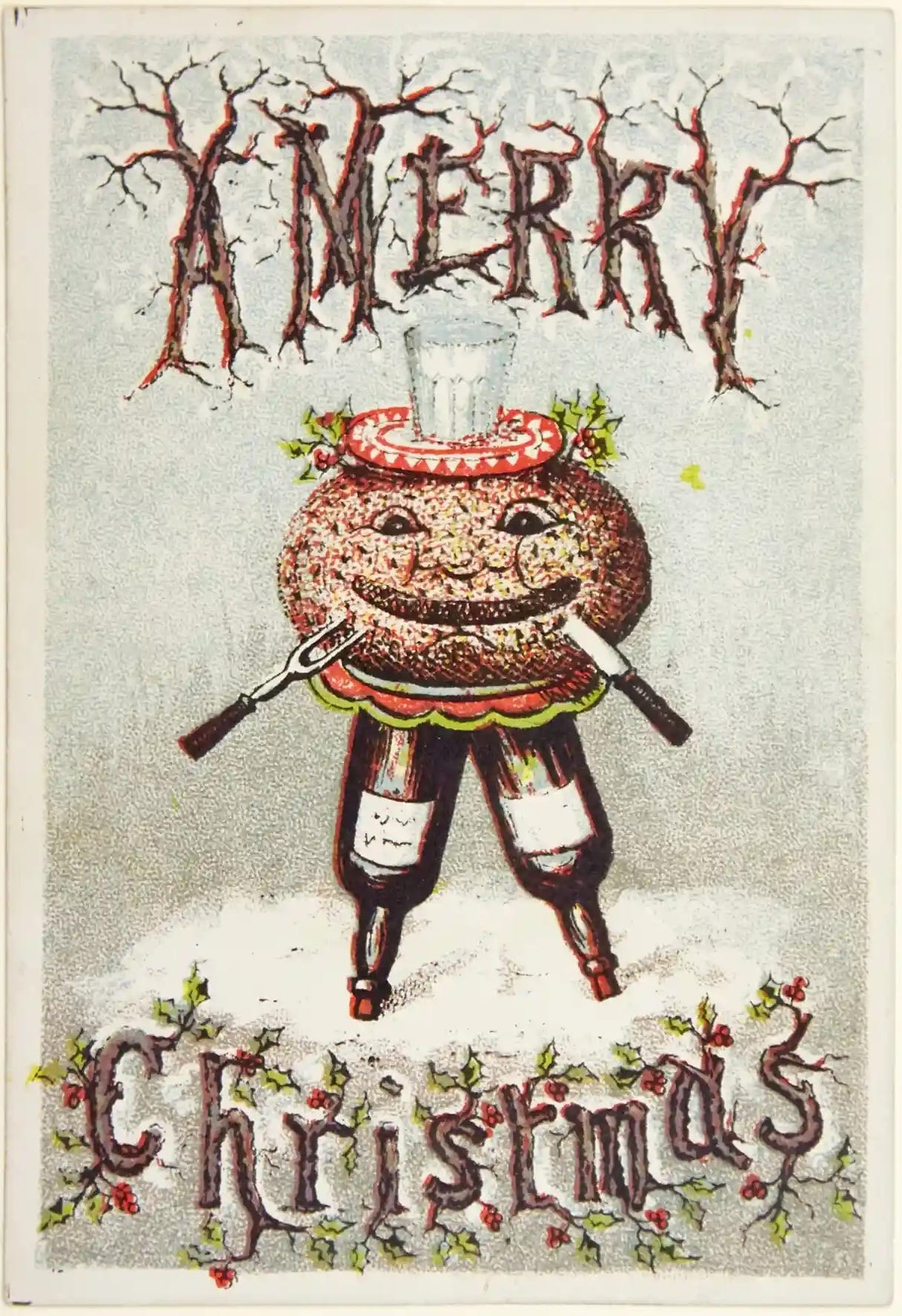

Setting the morose aside, some of the cards were cheerier, often anthropomorphizing the inanimate. For example, consider the Christmas pudding below.

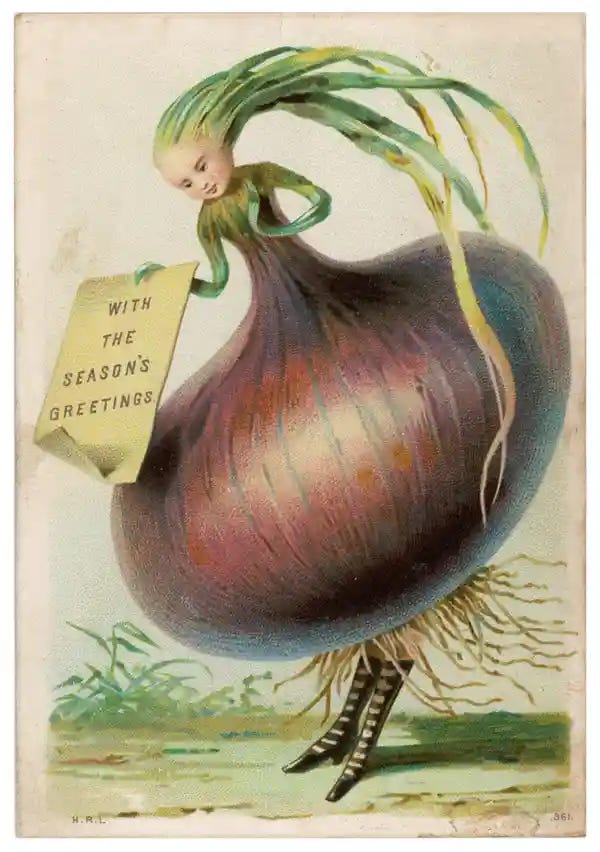

Or consider these anthropomorphized vegetables: an onion and a turnip wishing you a merry Christmas.

On the theme of humanizing the inhuman, many Victorian cards depicted anthropomorphized animals. These cards, some theorize, capitalize on the evolution craze sweeping Britain following the 1859 publication of Charles Darwin’s On The Origin of Species. Darwin’s book proposed the theory of natural selection and challenged pre-conceived notions of creationism. Origin became not only a scientific hit but also a popular text. Victorian society was obsessed with the idea of evolution, and if we evolved from monkeys, why couldn’t a beetle dance with a frog while a fly played a tambourine on a Christmas card!?

And some cards brought together these anthropomorphized animals with an anthropomorphized dinner: A true celebration!

Today, our Christmas symbols are codified. It’s the holiday of Santa, gingerbread houses, and snowmen. But, in the Victorian era, Christmas celebrations were still novel: Queen Victoria, who had recently married the German-born Prince Albert, only started decorating a Christmas tree in the 1840s, thanks to her husband’s German influence. It would take decades for a modern view of Christmas to crystallize in the public conscious of the English-speaking world. And, until that time, the holiday’s symbolism was a grab bag. There was no one way to celebrate the holiday, be it on a card or in real life. So, symbols proliferated, from dancing frogs to crazy clowns to smiling puddings.

They were all a way to wish you a merry Christmas…

…and a happy new year, too.