Our kitchens are filled with gadgets: Tea kettles, coffee makers, microwave ovens, pressure cookers. In 17th and 18th century Britain, one of the most useful kitchen gadgets wasn’t a piece of technology. It was an animal. The turnspit dog.

The dog, whose first use in the kitchen was documented in 1576, had one job: To run in a wheel. The wheel would be hooked up to a meat spit, and as the dog ran, the wheel rotated the spit so the meat cooked evenly in front of an open fire. The dog relieved servants –– known as “spit boys” –– from the arduous task of continually spinning roasts over the fire (a particularly common chore in royal kitchens because of the importance of roasts in British feasts). The dogs also helped with other culinary tasks including fruit pressing, butter churning, water pumping, and grain milling.

Charles Darwin cited the dogs as an example of genetic engineering, writing: “Look at the spit dog. That's an example of how people can breed animals to suit particular needs.” The dogs were related to terriers and looked something like the modern-day dachshund –– long-bodied with strong, crooked legs. They were perfectly sized to fit in the spit wheels and run endlessly, which is why Darwin cited them as an example of artificial selection. 19th century writer Edward Jesse described them as “ugly dogs, with a suspicious, unhappy look about them, as if they were weary of the task they had to do, and expected every moment to be seized upon to perform it.”

People treated the dogs as lowly kitchen tools whose only purpose was to ease the burden of kitchen labor (Queen Victoria being an exception, who kept three as house pets). The dogs would spend hours a day in the wheel. Smells radiated from delicious roasts the dogs couldn’t reach, and these dogs –– when stuck in their wheels –– weren’t supplied with water. The wheels were often close to the fire, so the dogs would overheat and their lungs would fill with smoke. Sometimes, cooks would put a hot coal in the wheel to make the dog move its feet more quickly. The repetitive running-in-a-wheel motion put strain on the dog’s long backs and often created chronic pain issues. This poor treatment led to the founding of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA) when the SPCA’s founder saw how the dogs were treated in 19th century Manhattan hotels.

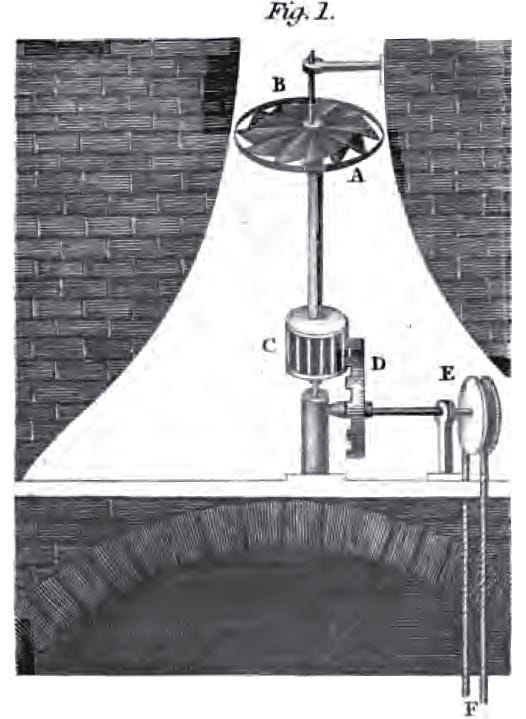

After 300 years of service, by the 1850s, the turnspit dog disappeared from kitchens. Today, the dogs are extinct. The extinction was driven by technological innovation. In 1853, author John George Wood wrote: “The invention of automaton roasting-jacks has destroyed the occupation of the turnspit dog, and by degrees has almost annihilated its very existence.” The roasting-jack was a weighted pulley that rotated a meat spit automatically, eliminating the need for the dog. The jack became the easy, high-tech tool of choice for roasting. Later, in the 1900s, gas ranges and electric kitchen equipment usurped both the jacks and the dogs as the preferred tools for cooking roasts. Keeping a turnspit dog became more of a hassle than switching on an automatic jack or firing up a gas range.

Today, we see dogs as lovable partners and adorable house pets. But this wasn’t always the case. We used to treat dogs as tools, as power sources. The turnspit dog was a piece of kitchen technology. And, when a better tool came along, the animal went extinct. Perhaps a good thing, though, because those poor dogs spent their days just running and running and running, smelling the roast but never being able to eat it.

Notes.

This is largely a compilation of a few articles on turnspit dogs: NPR, Kitchen Sisters, Modern Farmer, Atlas Obscura.

Jane Bondeson’s written a book on dogs in history that contains a section on the turnspit dog.