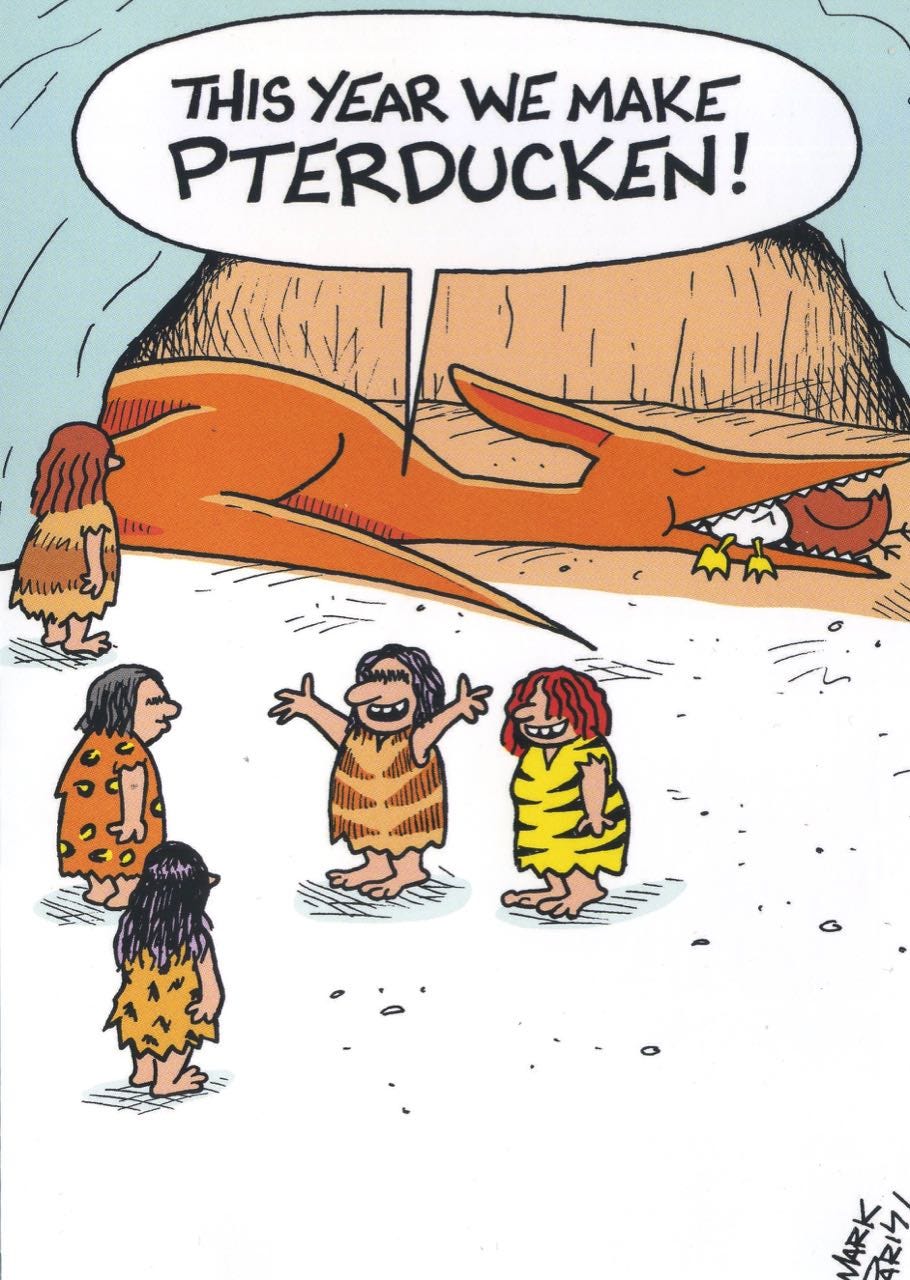

The turducken is a de-boned chicken stuffed inside a de-boned duck stuffed inside a de-boned turkey. This Southern dish is, perhaps, the most decadent of Thanksgiving entrees. “A well-prepared turducken is a marvelous treat,” writes journalist Amanda Hesser, “a free-form poultry terrine layered with flavorful stuffing and moistened with duck fat.” With turducken, there is no attempt at self-restraint; the dish embraces Thanksgiving and all its extravagances.

The name “turducken” (portmanteau of turkey-duck-chicken) was trademarked in 1986 by Louisiana chef Paul Prudhomme, who claimed to have invented the dish, but the idea of a bird-in-bird entree is much older than Prudhomme. For instance, an 1832 “preserve of fowl” dish from South Carolina consisted of a dove stuffed in a quail stuffed in a guinea hen stuffed in a duck stuffed in a goose stuffed in a turkey. (That’s a six bird entree.) Across the world, there’s an old feast dish from The Republic of Georgia that was a roasted ox stuffed with a calf stuffed with a lamb stuffed with a turkey stuffed with a goose stuffed with a duck stuffed with a young chicken. Seven animals, so many that “the art lay in ensuring that each type of meat was perfectly roasted,” according to food scholar Darra Goldstein. The best, though, is French lawyer Grimed de la Reyniere’s 1807 recipe for a “roast without equals.” Seventeen birds stuffed inside each other: a bustard stuffed with a turkey, a goose, a pheasant, a chicken, a duck, a guinea fowl, a teal, a woodcock, a partridge, a plover, a lapwing, a quail, a thrush, a lark, an ortolan bunting, and a garden warbler.

These dishes utilize engastration, a cooking technique in which the remains of one animal are stuffed into another. Engastration is an art, collapsing the line between function and entertainment. While the technique originated in Ancient Rome, it came into its own at the early modern European banquet table (c. 1400-1500). These banquets were elaborate events, often aimed more at impressing guests with the host’s wealth than serving something delicious. To accomplish this, banquet food often served as an important source of entertainment. Consider a recipe from a mid-15th century French cookbook that called for a chef to get a chicken, pluck its feather while still alive, paint it with a mixture of egg yolks and saffron, tuck its head under its wing until it fell asleep, and then serve it on a platter. Thus, when the chicken was about to be carved, it would “wake up and make off down the table upsetting jugs, goblets, and whatnot,” per the recipe. It was a living chicken served to look like a dead one. Certainly more entertaining than appetizing. Dining in a Medieval palace was often a game of deceit.

Scholar Karen Raber argues this chicken and the turducken are “performing meats.” In the case of turducken and other engastric meats, the performance comes from the layering, which acts as a cloaking device. The turkey conceals the duck and chicken, until it is carved. Then –– surprise! –– a single animal is revealed to be inhabited by others! The turducken extends from a long line of surprise theatrical foods served at early modern banquets. For instance, the court dwarf to Henrietta Maria, Jeffrey Hudson, was presented to her leaping out of a pie crust. And Pope Gregory XIII served a miniature castle model out of which came rabbits, partridges, and other animals.

Engastric “performing meats” like turducken are intentionally confused and confusing. Per Karen Raber, they exist because of “the mobile (in every sense of this word) thingness of a thing (dead flesh) that was once a living object (the animal).” In other words, the turducken is surprising and confusing because the nature of meat is surprising and confusing. Meat sits in a liminal state between being alive (the animal it came from) and supporting life (when you digest it). It is “mobile” because it is always in the process of transformation, from animal to flesh, flesh to meat, consumed meat to human flesh. And the turducken embraces this “mobility” by existing in an equally liminal state between three separate birds and one absurdist amalgamation.

By extension, the turducken is a construction, just as meat itself is a construction. Meat is a result of human intervention from agriculture to butchering to roasting. The turducken –– as the result of careful and fanciful preparation –– makes this process of human intervention very evident. The dish lays bare how humans shape what they eat.

In turn, the turducken requires us to see food not just as fuel for our bodies. In the early modern era, medical beliefs posited that human bodies were defined by the meat they consumed. Pork, for instance, was a low-class dish for crude bodies, while tender fowl was for refined individuals. Thus, if the identity of one’s dinner is confused –– a turkey? a duck? a chicken? –– any pre-conceived notions around “appropriateness” must be thrown out the window. Instead of affirming identities (e.g., pork = poor), “performing meats” like the turducken challenge identities. They violate the notion of clearcut categories by existing in many categories at once.

But, just as you’re about to eat the piece of turducken on your fork, all of this is stripped away. The performer takes its final bow. At this moment, the turducken is no longer an amalgamation of three birds –– it is just a piece of flesh about to become a part of your flesh. The performativity is gone once the meat is carved. The food becomes just sustenance.

I’m tempted to say the moment where you taste the food is the most important moment. But, dinner is just as much a performance as it is an opportunity to fuel up: The performance of cooking, the performance of carving, the performance of table setting, the performance of serving. All banquets –– be it in a medieval castle or at your Thanksgiving table –– are shows.

So, curtain up: It’s time for Thanksgiving dinner.

Notes.

The ideas in this post are largely drawn from Karen Raber’s “Animals At The Table” chapter in her book Performing Animals (2017). It’s a fascinating read and discusses so much more about early modern banquets and performing meats than I could get into.

In 2002, the New York Times published a lovely article on turducken here.

Other sources for turducken information include Taste of Home and KCET.