The Rolling Suitcase

Invention, gender norms, and why it took so long to put wheels on a suitcase

According to luggage lore, in 1970, American luggage executive Bernard Sadow had a “eureka” moment. On his way through customs after a family vacation, Sadow noticed how an airport worker could move a heavy piece of machinery effortlessly on a wheeled pallet. He contrasted this with his own experience, struggling to lug two heavy suitcases down a long hallway. Standing in the customs line, Sadow turned to his wife and said: “You know, that’s what we need for luggage.”

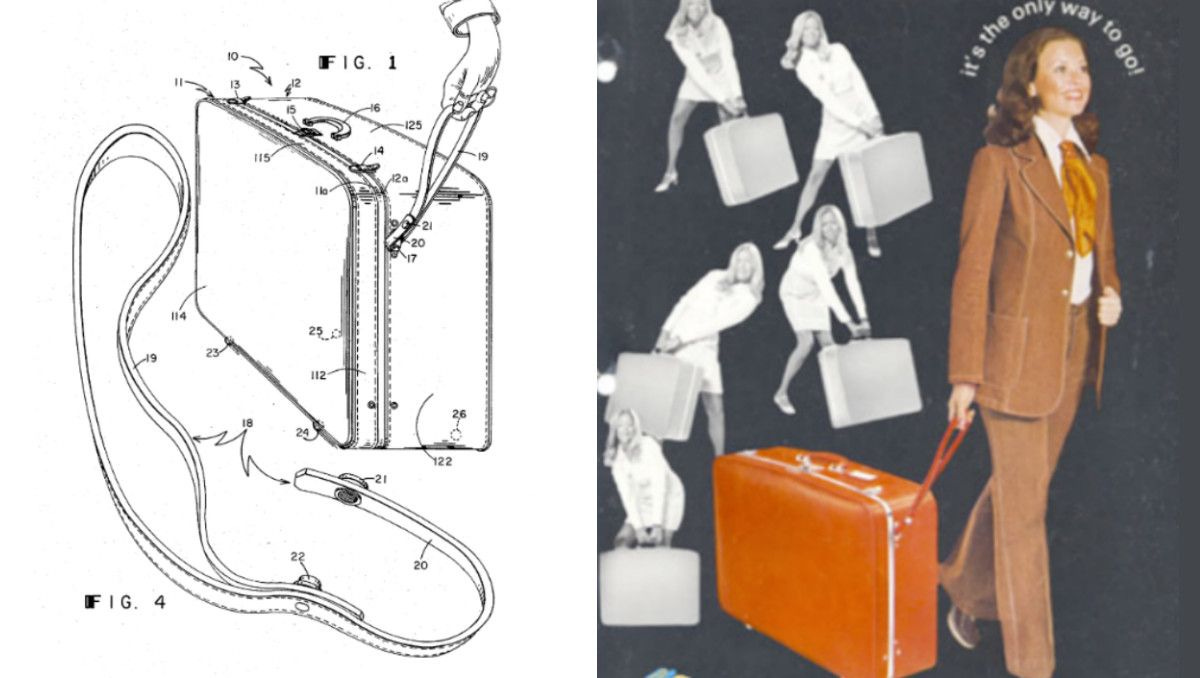

When he got home, Sadow unscrewed four wheels from a wardrobe and stuck them to the bottom of his suitcase. He attached a strap, and then he wheeled it happily around his house. The rolling suitcase was born.

Two years later, Sadow patented his design. In the patent, he made a grandiose claim: “Baggage-handling has become perhaps the biggest single difficulty encountered by an air passenger.” Sadow saw his wheeled suitcase as the solution.

However, the public didn’t agree. People didn’t buy the rolling luggage, in part because of Sadow’s design. Sadow’s suitcase was a four-wheeler towed on a leash in the horizontal position. A bit like taking an uncooperative dog for a walk. It wasn’t until 1987, when Northwest Airlines pilot Robert Plath developed the two-wheeler “Rollaboard” suitcase, that the rolling suitcase took off. The Rollaboard had telescopic handles and rolled vertically. Plath sold his early models to fellow crew members, and as travelers saw flight attendants striding through airports with Rollaboards in tow, a new market was created, normalizing the rolling suitcase as a traveler’s best friend.

If we stop the story here, this seems like a straightforward tale of an inventor solving a problem and then another inventor improving upon that solution. But it’s not that simple.

Luggage had been around for centuries. Wheels had been around for millennia. We’d even been putting luggage on wheeled carts in airports for decades. Why’d it take so long to put the wheels directly on the suitcase!?

According to research by economist Robert Shiller, innovation can be very slow –– especially when it comes to the very obvious. The answer might be so clearly in front of us that we overlook it. We sometimes ignore everyday problems, instead striving for the grand, difficult, and complex. We put a man on the moon before we put wheels on a suitcase. Often, we have trouble challenging the norms that define our everyday lived experiences.

When mass tourism first took off, railway stations and airports were inundated with porters who would help passengers with their bags. But, by the middle of the 20th century, changing labor patterns led to a decline in porters, requiring passengers to carry their own luggage.

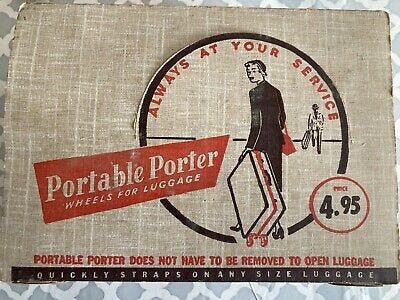

As early as the 1940s, you can find advertisements for products that combine the wheel and the suitcase –– called “portable porters,” they were wheeled devices that could be strapped onto suitcases.

But these gadgets didn’t catch on; they were considered niche products for women. The resistance to the “portable porter,” and later to the rolling suitcase, was deeply rooted in gender.

According to author Katrine Marcal, two assumptions about gender underly this perception of the rolling suitcase. First: Rolling a suitcase was “unmanly.” “Men used to carry luggage for their wives. It was the natural thing to do, I guess,” Sadow said when explaining why his invention didn’t succeed. On early sales calls, Sadow would often be told that men would not accept suitcases with wheels. “It wasn’t a very macho thing,” Sadow noted.

Second: While there was nothing preventing a woman from rolling a suitcase (she had no masculinity to prove), the industry assumed women never traveled alone. The industry assumed a woman would always have a man with her to carry her bags. This, Marcal argues, is why the industry couldn’t see the commercial potential of the rolling suitcase until the 1980s –– when women, increasingly, began traveling alone. The rolling suitcase rode in on the heels of greater mobility for women.

So, the rolling suitcase didn’t align with mid-20th century views on masculinity. The rolling suitcase was not fully embraced by the industry (and, in turn, by consumers) because it overtly challenged the norms of the era.

This, perhaps obviously, isn’t unique to the suitcase. For instance, in the 1800s, when electric cars first emerged, they were seen as “feminine” because they were slower and less dangerous than gasoline-powered vehicles. This perception, in turn, hindered the development of electric cars and helped fuel (sorry for the pun) the growth of the gas-guzzler. Today, we can see this dynamic playing out with the impossible meat industry, where plant-based burger patties challenge the perception that “real men eat meat.”

These norms are everywhere. They exist like a fog, obscuring our view of the obvious, of opportunities for innovation. In turn, these norms are sometimes the hardest things to challenge. Sometimes the everyday –– what we’re so used to –– can be the hardest to reinvent. But perhaps that’s why it’s the most ripe for reinvention.

Notes.

This post is largely inspired by Marcal’s book on women and innovation, Mother of Invention. She wrote a piece on the rolling suitcase for The Guardian here.

I discovered Marcal’s book while waiting for a sandwich at La Grande Orange in Phoenix, AZ, in December. So this post is largely indebted to that wonderful establishment (and their long delay making my sandwich during a busy holiday season).

Another interesting Guardian article on the history of wheeled luggage here.

And The New York Times wrote one on wheeled luggage, too.

Nassim Nicholas Taleb, the essayist, offers an interesting take on how the suitcase illustrates the delayed relationship between innovation and implementation here.