Of all the things we take for granted about air travel, perhaps top of the list is that planes take off and land on runways. But, in the early 20th century, it looked like the future of air travel might’ve taken a different turn –– one based on the water.

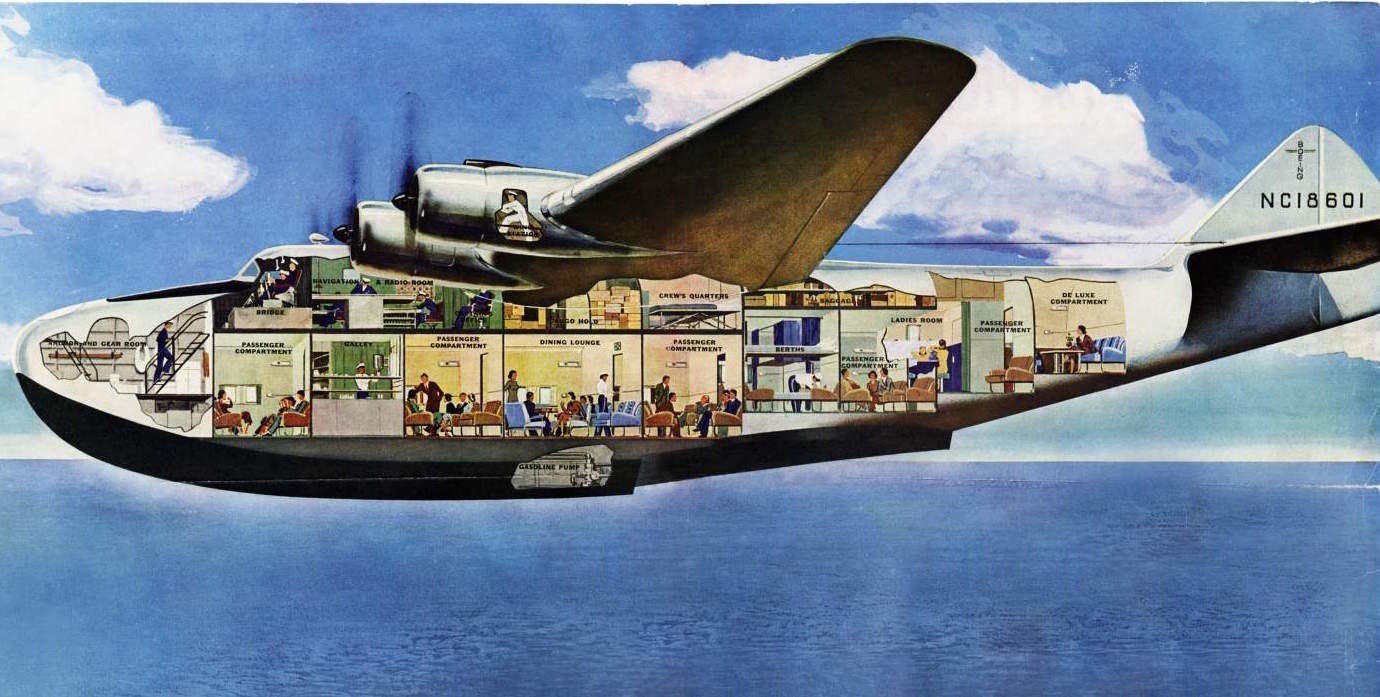

In the 1930s and 1940s, air travel was all about the flying boat. The boats –– operated by airlines around the world, including Pan-Am (USA) and Imperial Airways (UK) –– each carried a few dozen passengers in spacious cabins.

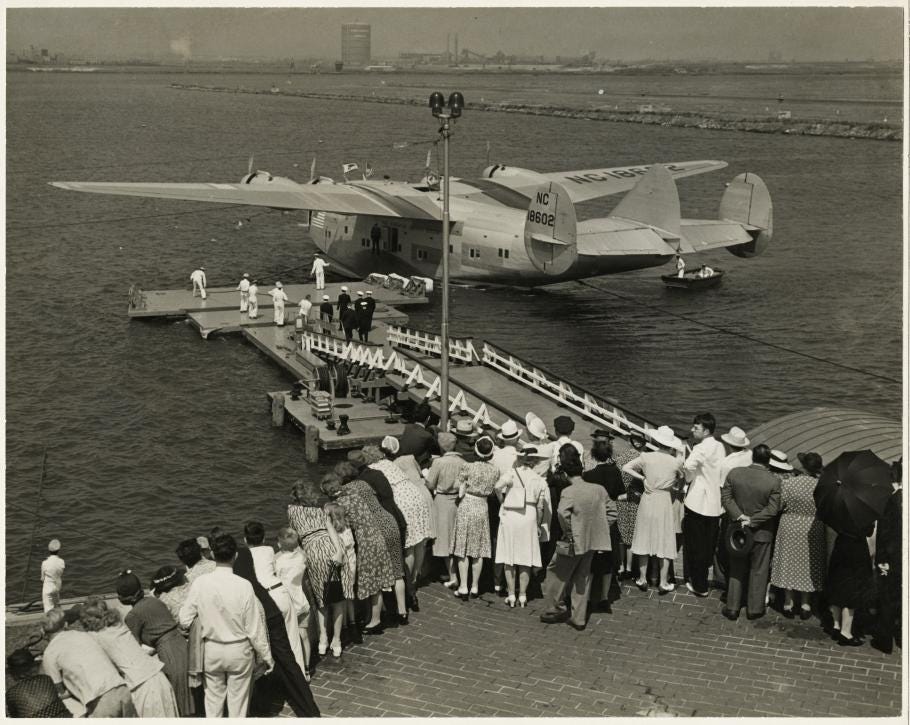

Despite their small passenger count, these boats were very heavy. They often weighed upwards of 75 tons (which is almost double the weight of a modern Boeing 737). The biggest aircraft in the 1940s was a 100-ton, six-engine flying boat built in Germany. Because of their huge size, these boats required large waterways and harbors for takeoff and landing; prime locations included Lake Victoria in east Africa and the East River in New York. In 1939, NYC’s LaGuardia Airport actually opened the Marine Air Terminal specifically for overseas travel on flying boats.

At the time, land-based airport infrastructure couldn’t handle planes this large. They would’ve needed long concrete runways to take off, and 1930s airports only had short grassy strips.

Thus, people saw flying boats as the future of long-distance aviation –– so much so that the Director General of Imperial Airways suggested building a giant lagoon for landing flying boats alongside the runways at the new Heathrow Airport.

The flying boat was the airplane of choice. In the late 1930s, Imperial was operating forty flying boats, versus only twelve landplanes of the same size. And, beyond commercial travel, World War II gave a massive boost to the flying boat industry, largely because the flying boat was very useful for naval reconnaissance. The Japanese military built more than 150; the USA, over 200; the UK, over 700.

But the Second World War –– the same force that led to the expansion of the flying boat –– also led to its decline.

Modern warfare became increasingly dependent on aerial bombardment, and hard runways increased maximum take-off weight and hence the load of bombers. The plane industry knew this before the war, but the high cost of building these runways was prohibitive. However, the War shifted priorities, and governments around the world started investing in runways.

Therefore, long concrete runways were built to accommodate heavier and heavier planes. The flying boats couldn’t compete. Not only were the boats less efficient in the air than landplanes, but there wasn’t enough protected water for the huge number of wartime bombers to safely takeoff and land.

The rise of the land-based aircraft was rapid, once people realized its advantages. In the words of historian David Edgerton: “[The flying boat] represented the peak of aviation in a world with few flights and few runways, but it could never have sustained the phenomenon of mass civil aviation which emerged in a newly concreted world.”

In 1939, there were only nine hardtop runways in the UK; by 1945, there were hundreds. As runways became more prevalent and the cost of running landplanes decreased, airlines shifted. Pan-Am dropped flying boats in 1946; Imperial in 1950. Some flying boats were still built and used in the 1950s –– largely for firefighting missions –– but today they’re novelties, not the norm.

Note.

This is adapted from David Edgerton’s entry on the flying boat in Extinct: A Compendium of Obsolete Objects. It’s a lovely book with entries on many interesting, obsolete objects.