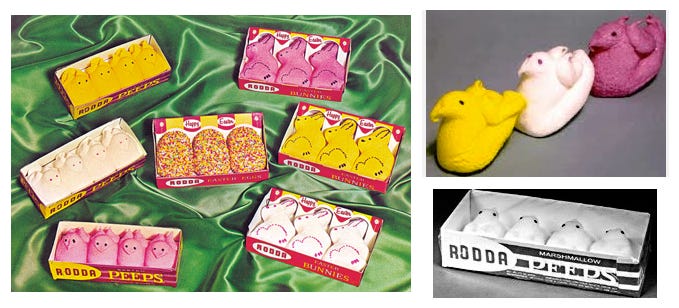

In the early 20th century, Rodda Candy Company was searching for a way to distinguish itself in the crowded candy industry. So, the company turned to Easter treats. First, they developed a line of chocolates in religious shapes such as crosses and eggs; then, they branched out into marshmallow candies in the late 1940s.

The Peep was born.

In these early years, Peeps were made by a team of around eighty women, most of them German immigrants, given the large German population in Pennsylvania. The women would spoon small batches of freshly-made marshmallow batter into pastry tubes and then squirt them out into the shape of baby chicks. The chicks were then air dried. It took upwards of 27 hours to make one tray of these Peeps.

Until the company was bought by Just Born, Inc. in 1953. Bob Born, who ran Just Born, spent nine months researching and designing a Peeps manufacturing machine. He studied the movements of the people who filled the marshmallow tubs and squeezed the pastry tubes. Reflecting on this R&D process, Born said in a 2003 interview: “We made so many samples, at first some of them coming down the line looked like seals. So we [kept iterating].” Finally though he built the “Depositor,” an automated machine that produced six rows of five Peeps at a time. It could do so in six minutes. Just Born was producing Peeps at a rate of 4.2 million a day.

In 2023 alone, Americans will buy over one billion Peeps. And they’re not just for eating. One survey found that 30 percent of people use Peeps for non-consumptive purposes: They’re put in centerpieces, turned into dioramas, and sewn into clothing. Food journalist Corby Kummer writes: “The Peeps’ mute, fixed expressions, flexibility, and curious properties –– they can be cut with scissors, stacked and used as craft materials, and inflated in microwave ovens –– have made Peeps a subject of fascination that has little to do with actually eating them.”

Of these curious properties, zoomorphism –– assigning animal-like qualities to non-animal objects –– sits at the heart of our Peep obsession. These little snacks, with their plush bodies and cute eyes, practically beg us to engage with them emotionally. Perhaps it’s why Peep diorama contests are popular. The little dudes lend themselves to serving as actors in dioramas. Just look at the cynical grin on the Sweeney Todd Peep or the sad state of the decapitated victim Peeps.

This zoomorphism might also be why Peep jousting is popular. In Peep jousting, two Peeps are stuck with toothpicks and placed near each other in the microwave. When the microwave is turned on, the Peeps expand, and the winning Peep pops the losing Peep first with its toothpick. The human onlooker becomes invested in these creatures, rooting for a winner and a loser. It’s hard to believe people would become this invested with classic marshmallows.

On top of this, Peeps last. In 1999, a team of scientists at Emory demonstrated that Peeps resist dissolution in water, acetone, sodium hydroxide and sulfuric acid. Even when left out, a single Peep won’t rot or grow mold. It will just dry out, retaining its shape and color.

It is the pairing of zoomorphism and indestructibility that, I’d argue, makes Peeps a cultural staple. Animals die; Peeps do not. An individual Peep will last nearly forever. And, sure, they are an ephemeral holiday treat, but they are also perennial. We know Peeps will resurface every year. They are always there with their bright colors and cute beady eyes staring at you from within their plastic packaging. Because of this certainty, we can plan our dioramas months in advance and get excited for our jousting tournaments. When so much can be fleeting, Peeps are dependable both as a perennial species and as indestructible individuals.