For centuries, we’ve wanted to scare away the dark. In Ancient Rome, wealthy citizens used vegetable oil lamps to light the front of their homes. In 1417, the Mayor of London ordered all homes to hang lanterns outdoors after nightfall in the winter. In 1816, Baltimore was the first American city to install gas streetlights.

And, by the mid-19th century, Americans used electricity to fight the dark night. At first, cities tried construct grids of electric lamps that mimicked and repurposed gas lamps, but this required lots of wires, which would often fall onto the streets below. In other words, these grids were a mess: inconvenient, dangerous, expensive, and time-consuming to install.

So, in the quest to find cheap, quick ways to bring light into the night, cities looked up. And they decided to mimic the moon.

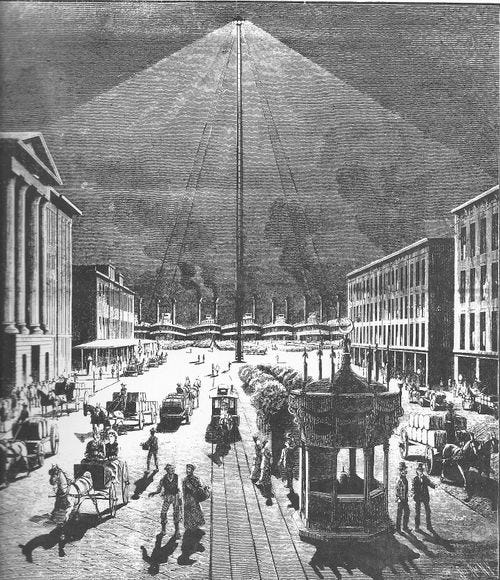

The “moonlight tower” was a 250-foot tall tower that looked like an oil derrick and was topped with 4 to 6 arc lamps. In 1877, when arc lamps were developed for mass production, they were the brightest source of light around: Their glow was equivalent to 6,000 candles. Compare that to a gaslight, which had a glow equivalent to 16 candles.

When a tower was illuminated at night, it looked as if an artificial moon glowed above the city streets. One observer described the towers as “picturesque and romantic.” He said: “All places within the scope of light are bathed in the faint but fairy-like illumination of the moon in its first-quarter.”

Thanks to these towers, artificial moonlight blanketed cities across America in the late 1800s. You could find them in Austin, San Francisco, Denver, New York, and Los Angeles. Detroit, perhaps, was the most committed to the technology. In 1888, the city constructed a network of 122 towers, each 175 feet tall, that covered more than 20 square miles of the city.

However, these moonlight towers weren’t perfect solutions to lighting the night. Moonlight towers are effective in open (low-built) areas where there are no buildings or trees to cast shadows that get in the way of the light. But, obviously, most cities have buildings that cast shadows and obscure the artificial moon, a situation that was made even worse by the development of skyscrapers in American cities. Thus, much of the city would be stuck in shadowy darkness, the light of the tower blocked by buildings. And, air pollution from an ever-industrializing nation added a haze to city air that also blocked the artificial moonlight. Cities were stuck in an eery gloom –– one that the towers were unable to dispel.

The rise of skyscrapers and air pollution coincided with advancements in the incandescent light bulb. So, when the moonlight tower proved useless, street-level lighting came in to save the day. Thanks to the incandescent bulb, it was now easy, affordable, and inoffensive to install street-level lighting around a city.

Thus, in Detroit for example, the towers were taken down within a decade of their construction. Today, only Austin, Texas, has standing moonlight towers. The city is dotted with thirteen of them, each kept in original condition except for the addition of a historic plaque noting its significance. These towers originally came to Austin from Detroit, after that city gave up on the lighting system, and in 1993, Austin spent $1.3 million restoring all of its towers. They stand more as historical relics than practical objects; Austin, like most modern cities, has street-level lighting, too. (You might’ve seen one of Austin’s towers featured in Dazed and Confused. It was the site of the high-school keg party.)

The poetic appeal of the moonlight tower –– a personal moon for every town –– remains strong. In 2018, the Chinese city of Chengdu announced a plan to build an artificial moon to illuminate the city. (They haven’t actually done so yet.) And, closer to home, the legacy of the moonlight tower lives on in the floodlight, which bathes sports fields and parking lots in a sea of light, blurring day and night. Our moons continue to shine bright.

Notes.

This piece is an amalgamation of information pulled from articles on moonlight towers from The Atlantic, Low Tech Magazine, and Extinct: A Compendium of Obsolete Objects.

More on Austin’s remaining towers here.