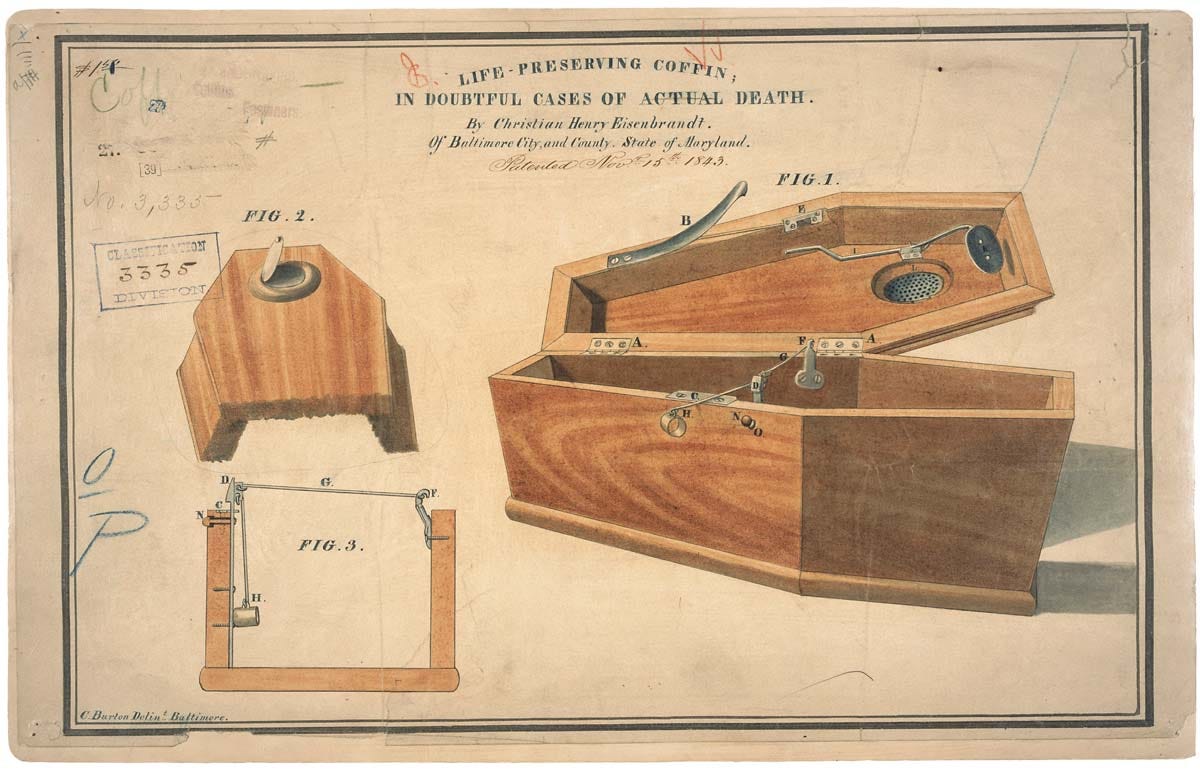

Life-Preserving Coffin (In Doubtful Cases of Actual Death)

A macabre moment for your Halloween Monday

[Content warning: This post discusses death and the act of dying.]

How do you know when somebody is dead?

Until measuring heart beats became common in the 1900s, doctors debated the best way to determine death. Some would subject the body to extreme pain to test for a reaction –– this might include slicing the the feet with razors or jamming needles underneath the toenails. But the most common method involved observing putrefaction. Bodies were left for days or weeks until signs of decay set in. As noxious odors would permeate the room, a person would be declared officially dead. This practice was so prevalent that in the 19th century Europeans could pay to have their loved ones body stored in a “waiting mortuary,” where corpses would be watched over until the telltale signs of decay set in.

This general uncertainty around when a body was “officially dead,” coupled with a Western cultural desire to bury bodies promptly, led to a paranoia that someone might accidentally be buried alive. And there are a few (only a few) documented cases of just that –– seemingly dead people coming back to life hours or days later.

Enter the “Life-Preserving Coffin (In Doubtful Cases of Actual Death),” an invention designed to prevent the burial of a living person.

The Life-Preserving Coffin, patented in 1843 by American musical instrument manufacturer Christian Eisenbrandt, is based on a series of springs and levers. The slightest movement from within would cause the coffin to burst open. As Eisenbrandt wrote in his patent: “Any one who may not really have departed this life may by the slightest motion … cause the instantaneous opening of the coffin-lid.” The person could escape unharmed! Or, in the words of the coffin’s advertisement: “[This] circumstance … entirely relieves the confinement of the body, and thus removes all uneasiness of premature interment from the minds of anxious friends and relatives!” (Obviously, this only works if the coffin is stored in a mortuary for a few days before burial, just to confirm death.)

The coffin’s advertisement goes on to say: “As most physiologists have agreed that there is no one certain sign of death, great difficulty must arise in distinguishing between a living and a dead body. … In consequence of the difficulty of establishing any positive, unerring signs of death, many individuals have been consigned to the grave before they were actually dead, is a truth too well tested to admit.”

This coffin stems from a confluence of a culture that feared death and a medical practice that hadn’t fully defined death. It seizes upon a paranoia around being accidentally declared dead –– a paranoia that has since dissipated as medical advances have allowed physicians to declare, with ever-increasing certainty, when a person is actually dead.

But even so, declaring death isn’t that simple. Today, for instance, physicians debate what constitutes “brain dead.” This sort of neurological death –– in which a person will never regain consciousness or be able to breathe without support –– is much trickier to define than physical death. In an ethics conversation on the topic in 2017, Johns Hopkins neurological care specialist Adam Schiavi said: “Most people have this notion that you’re recognizably alive and then you’re recognizably dead. However, what’s happened is that our technological ability to sustain life has moved faster than our moral capacity to deal with the implications.” Medical advances that once made it easier to define death are now complicating the line between living and dead.

Death is never as simple or clearcut as we might think. Just ask a vampire on this spooky Halloween evening… 🧛

Notes.

This post is inspired by this tweet from the National Archives, which I saw this morning.

The patent for the Life-Preserving Coffin is here.

A lot of the information cited is sourced from this advertisement for the patent.

Miranda Fortenberry’s paper on the coffin and Mary Roach’s wonderful book Stiff served as helpful references. If you haven’t read Stiff, you should –– it’s excellent.

The full JHU panel can be seen here.