You’ve probably seen this photograph. It’s a look into deep space. The photo, taken on June 3, 2022, captures the edge of the Carina Nebula, one of the largest star-forming regions in the Milky Way.

The Nebula is 7,600 light years away –– in other words, it would take 7,600 years traveling at the speed of light to go from Earth to the Carina. Put another way, this photo captures the Carina Nebula not as it exists today but as it existed 7,600 years ago. The light recorded in this photo left its source before the Egyptians built the pyramids. At that time, humans were just developing agriculture.

This all seems mind-boggling… but is this image fake!?

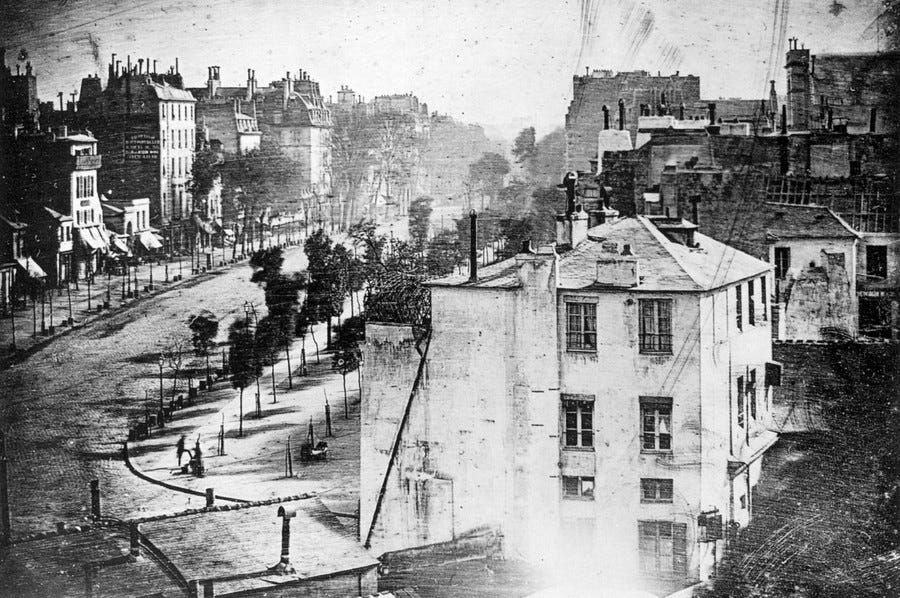

On a cold January afternoon in 1839, François Arago (secretary of the Academy of Sciences in France) described Louie Daguerre’s first photograph to the Academy. Daguerre’s photograph captured a Paris street scene, and Arago celebrated the photo’s resemblance to nature, noting its “truth of form,” “exactitude,” “fineness,” and “almost mathematical precision.” After Arago’s remarks, physicist Jean-Baptiste Biot took to the stage. Biot declared photography an “artificial retina” and celebrated its potential to facilitate new physics research.

By comparing photography to the eye, Biot connects the new medium to one of science’s oldest desires: Developing an objective way to observe and capture the world. Our eyes are how we observe the world, and since the days of Plato, people have been trying to create a mechanical super-eye that could both see and remember. The camera can do just that.

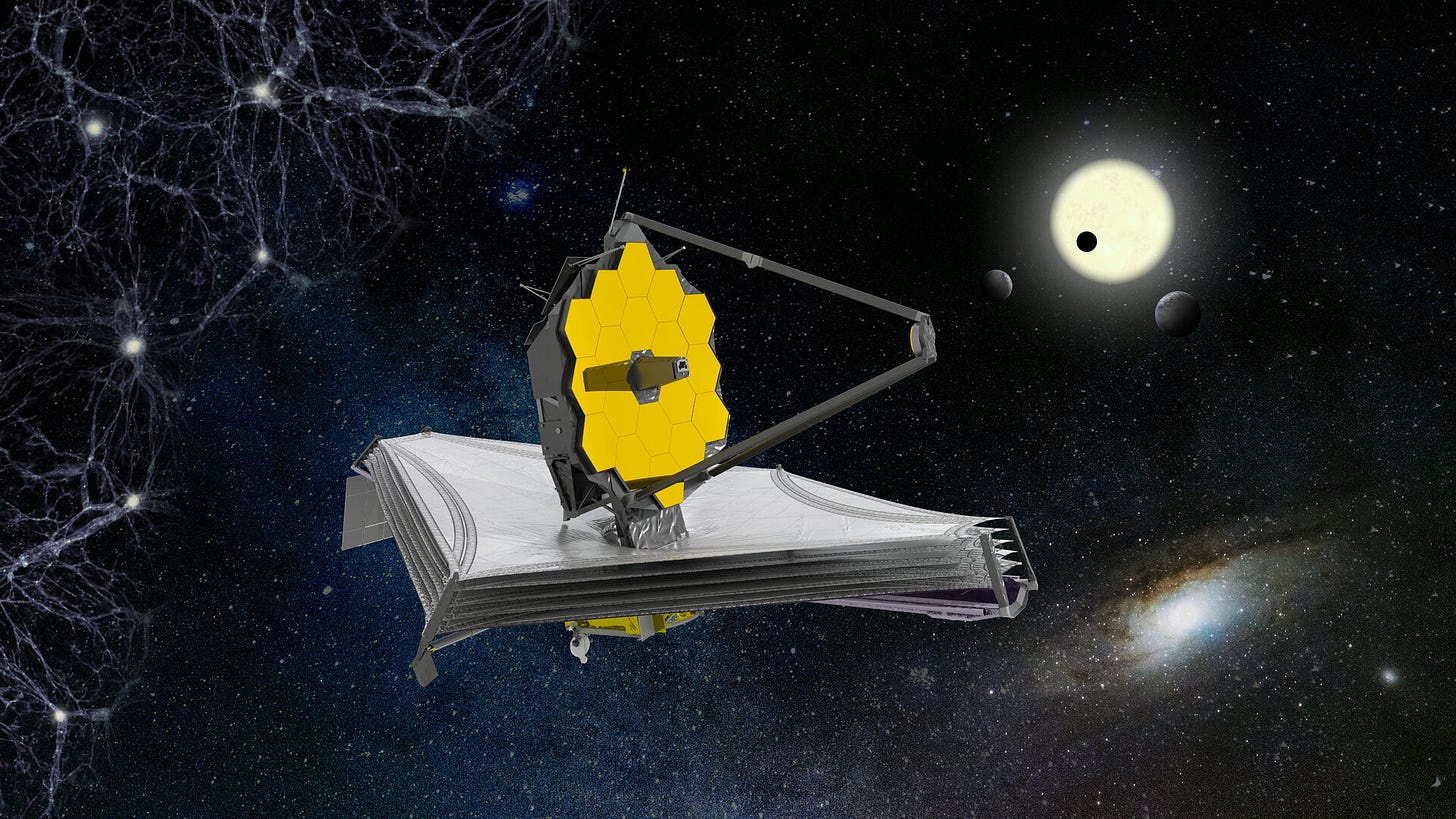

As can the James Webb Space Telescope. This telescope can see and capture more than its predecessors. Unlike older telescopes, the Webb can capture not only visible light but also infrared light. It has sunshields to avoid protect it from stray light from the Sun and a 21-foot long mirror that captures light. In other words, the Webb is more powerful than the human eye, both in physical size and in its ability to see. It is the ultimate super-eye, the ultimate “artificial retina.”

To Arago and Biot (whose remarks served as the public’s first introduction to photography), photography was an objective observer of the world, free from bias and error. Arago and Biot promoted this perception of photography because it coincided with a 19th century culture of scientific observation that valued absolute objectivity. Because photography was seen (rightfully or not) by scientists and non-scientists as technically indefatigable and optically reliable, people embraced the medium as the best way to capture an objective observation, something 19th century scientists valued –– and 21st century scientists still do.

But this idea of photography capturing something “true” is false.

Our ability to see the Carina Nebula depends on the manmade Webb telescope. Sociologist Michael Lynch notes: “What scientists perceive and work upon is artificial in the extent to which its appearance depends upon such technologies.” This artificiality isn’t a bad thing. Often, it’s a necessity. For instance, if you don’t have a telescope that can capture both visible and infrared light, there are “truths” about the universe you’ll never see. You can’t fully see the natural Nebula without the artificial telescope.

This artificiality exists not only with the technology but also in the image itself. Per Lynch: “The artificial appearance of a specimen is what enables it to be observed and analyzed in the first place.” The famous Webb photo of the Carina Nebula photo isn’t actually one image. It’s a composite. As NASA explains on their website, “several filters were used to sample narrow and broad wavelength ranges, [and] the color results from assigning different hues (colors) to each monochromatic (grayscale) image associated with an individual filter.” In essence, the colors we see aren’t real. Rather, they were applied to the image as a filter. The entire image, therefore, is a construction: Made by a complex telescope, made from multiple exposures, and colored by a computer. Or, put another way, the image doesn’t capture something as it literally exists in the world. Without the Webb telescope and the team’s manipulation of multiple images, you wouldn’t be able to see this view of the Nebula.

Science, in turn, is a constructive activity. The Webb photo is not a straight observation of a faraway galaxy. What we see in this image is neither wholly fake nor simply natural. Rather, in Lynch’s words, science comes from “an encounter between a rational mind and an inherently orderly nature.” In the Carina Nebula image, we are seeing something that exists in the world, but we couldn’t see it without tools we invested countless hours in constructing.

Does that make this image less real or less true? I’d argue it doesn’t, but it does center this seemingly-objective observation on something manmade. The path to understanding nature often crosses through the artificial.

Notes.

Sergio Pecanha’s Washington Post opinion piece on the telescope (for some of the information on the JWST)

Theresa Levitt, “Biot’s Paper and Arago’s Plates: Photographic Practice and the Transparency of Representation”, Isis, 2003 (for early debates surrounding photography’s objectivity in science)

Michael Lynch, “Discipline and the Material Form of Images: An Analysis of Scientific Visibility”, Social Studies of Science, 1985 (for understanding objectivity and artificiality in scientific images)

Kelley Wilder, “Photography and the art of science”, Visual Studies, 2009 (for the perpetual tension between photography as art and photography as science)

To see all of the photos taken by the JWST, go here.