Hummus: Part 1 – A History

On how a chickpea paste constructed a national identity for a new nation

Hummus is a spread of pureed chickpeas and tahini (sesame paste) created by Middle Eastern Arabs in the 13th century. It’s a simple, old dish — though the dish’s place in Israeli culture is anything but…

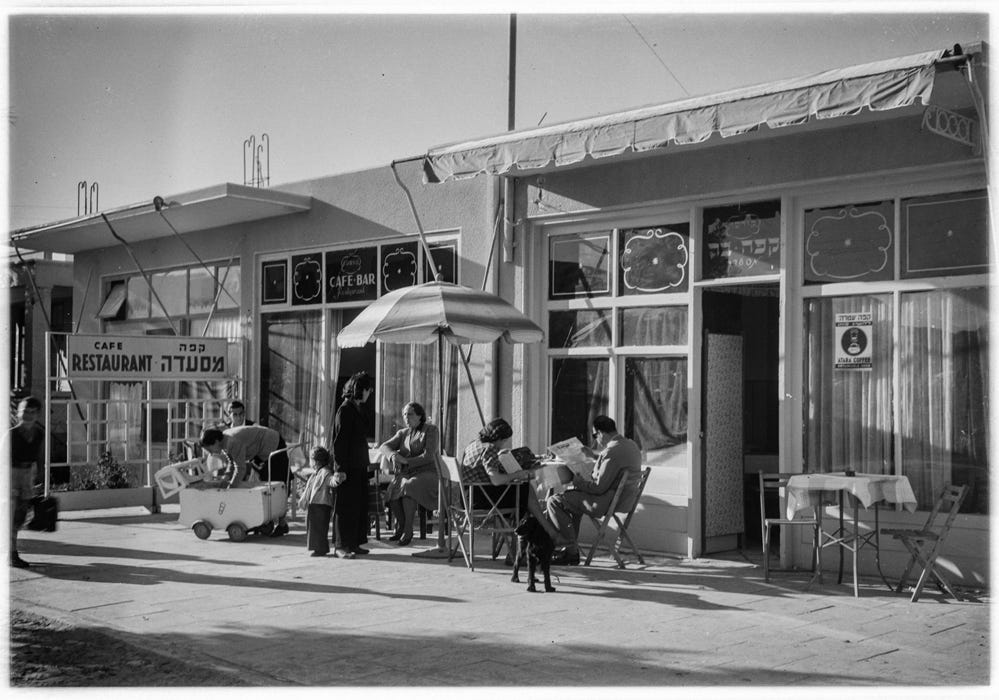

In the 1950s, Israel’s first decade, Mizrahi Jews from across the Arab world immigrated to the new nation. Because of this influx, a new type of restaurant emerged: Mizrahi restaurants, casual spots serving Middle Eastern food and operated by Middle Eastern Jewish immigrants. Hummus was a staple on these menus.

However, Mizrahi Jews didn’t eat hummus before arriving in Israel. Hummus was consumed mainly in Lebanon, Jordan, Syria, and Palestine, and these Jews came from North Africa, Yemen, and Iraq.

Thus, the Jewish embrace of hummus was a mark of nativism. By eating hummus, Jews — no matter where they came from: Europe, the Middle East, elsewhere — could become “locals,” which was ideologically important for the Zionist movement.

Over time, as these restaurants served more and more hummus, the food was naturalized into Israeli culture, estranged from its Arab past and attached to an imagined Middle Eastern Jewish cuisine. Hummus was incorporated into Israeli culture as an “authentic” Jewish-Israeli food, even though its roots were Arab, not Jewish.

Hummus’ rise to prominence as an Israeli dish happened not only in artisan restaurants but also through the food industry. Supermarket hummus was everywhere in mid-century Israel, and it became an agent for furthering a new national identity.

For instance, consider Telma hummus, released in 1958. Telma canned hummus was a huge hit: In 1962, Telma sold its 500,000th can. Six years later, they were on their 15 millionth.

In their marketing, Telma framed hummus as an Israeli food. No mention of Arab origins. In one publicity campaign, Telma said: “Knish or verenikas. Not all your guests are familiar with these eastern European dishes. But everybody eats hummus enthusiastically – hummus, the Israeli national dish.” Capitalizing on Jewish immigrants’ desire to become “locals,” Telma marketed hummus’ connection to Israeli identity. This is what scholar Michaela DeSoucey calls “gastronationalism” — the use of food to sustain the emotive power of national attachment. The food industry intentionally and explicitly tapped into a tie between Israel and hummus.

By the turn of the 21st century, hummus was well-established as an Israeli dish. Perhaps even the Israeli dish. In a 2005 survey of over 500 Israelis, hummus was chosen as the “most Israeli” industrial product. Another study that same year found 95% of all Israeli households have a tub of hummus in their fridge. Hummus had ingrained itself in the Israeli consciousness. It became, and remains, a symbol of the nation.

Notes:

Avieli, Nir. "The hummus wars revisited: Israeli-Arab food politics and gastromediation." Gastronomica 16.3 (2016): 19-30.

Hirsch, Dafna, and Ofra Tene. "Hummus: The making of an Israeli culinary cult." Journal of Consumer Culture13.1 (2013): 25-45.

Hirsch, Dafna. "“Hummus is best when it is fresh and made by Arabs”: the gourmetization of hummus in Israel and the return of the repressed Arab." American Ethnologist 38.4 (2011): 617-630.