At the turn of the 20th century, about half of the United States’ workforce lived on farms. Candy makers at the time, catering to demand, created products that appealed to farming sensibilities: There were candies molded into natural and plant-inspired shapes, such as chestnuts, turnips, clover leaves, and –– yes –– corn. Candy corn, though, stood apart from its confectionary peers because of its tri-colored design.

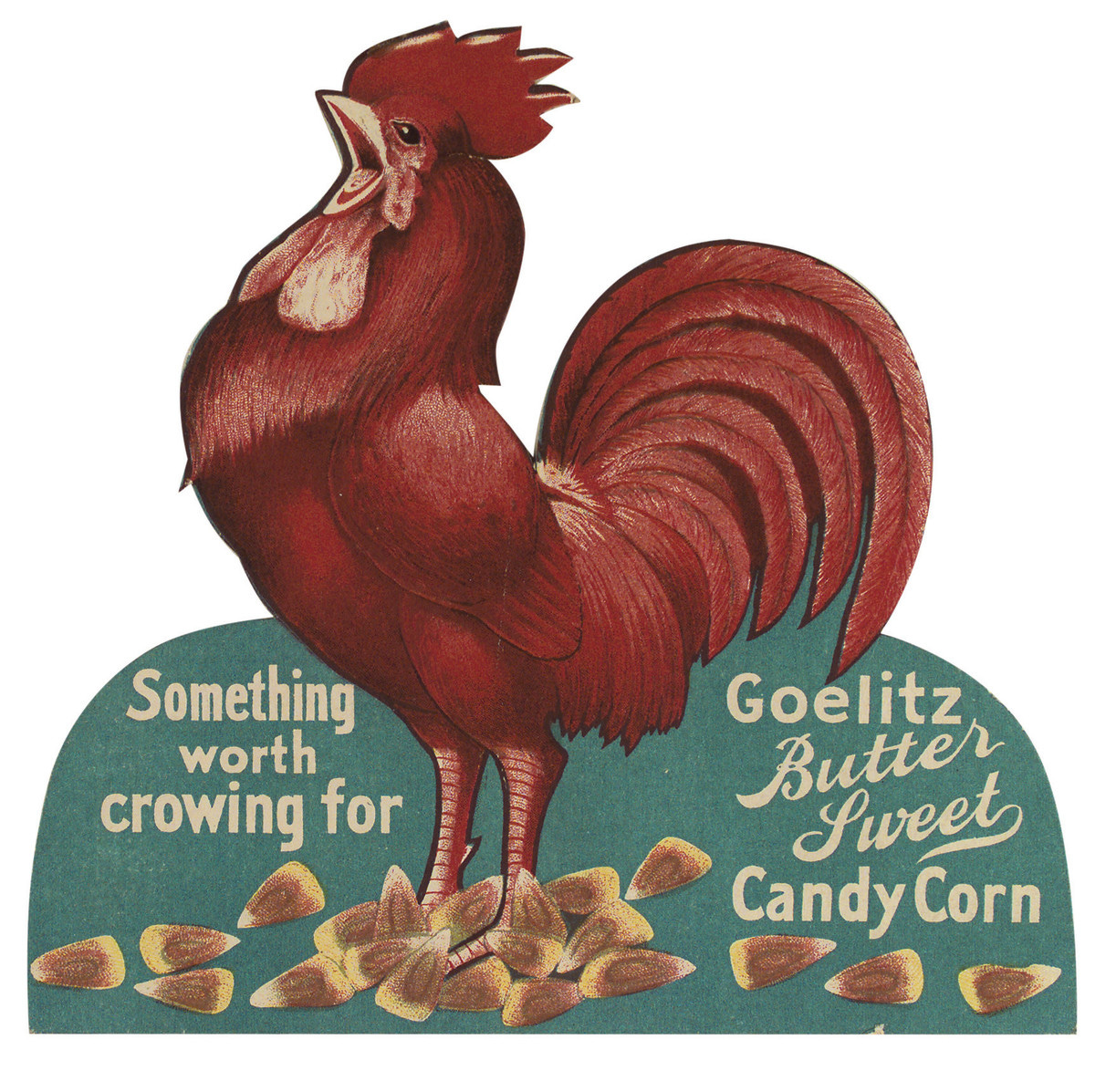

In the early 20th century, Americans didn’t eat corn (the vegetable). It’s texture was coarse, and there were no sweet hybrids. Thus, corn was fed to pigs and chickens. Because of this, candy corn earned the moniker “chicken feed” and, in turn, early marketing for the sweet often included roosters (see 1898 packaging above).

To some degree, Americans’ consumption of candy corn pre-dates consumption of corn itself; most people in the US didn’t eat significant amounts of corn until wheat shortages during World War I basically forced them to start cooking with corn flour and corn meal. Candy corn, though, was popular as early as the first decade of the 1900s. It was so popular, in fact, that in the early 1900s, manufacturer Goelitz had to turn down candy corn orders because of production capacity limits.

As the 20th century wore on and Americans moved away from farms and into cities and suburbs, candy corn became a popular “penny candy,” the sort of treat often bought in bulk at discount store candy counters alongside Tootsie Rolls, Necco Wafers, and Hershey’s Kisses.

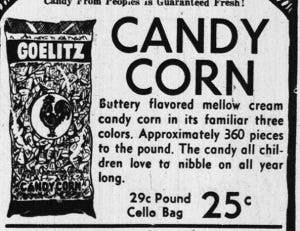

Candy corn was a year-round treat. It was featured in advertisements for summer candy and celebrated in marketing campaigns as a treat “children love to nibble on all year long” (see the ads above and below). It’s worth noting, too, how –– even once urbanization was in full swing –– the rooster persisted in some marketing of the candy.

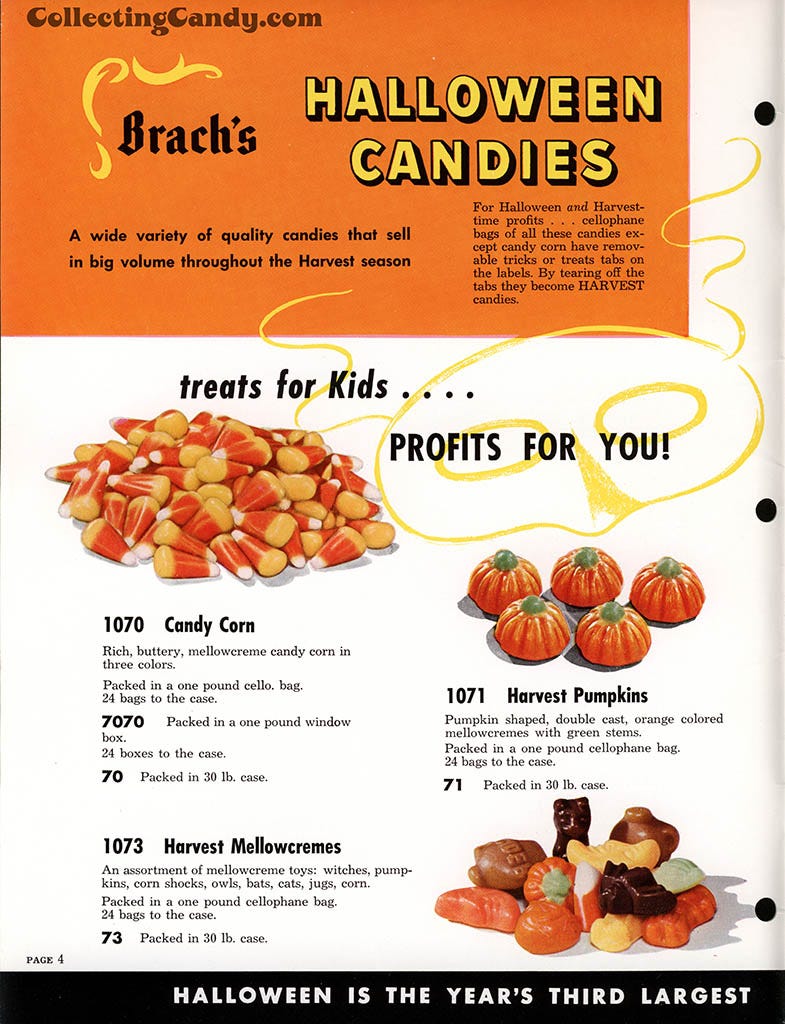

At the same time, candy corn’s identity as “the Halloween treat” was coming to fruition. Candy historian Samira Kawash hypothesized the association between autumn and candy corn arose in the early 1900s because of the candy’s coloring, which evoked the fall harvest. Marketing efforts in the mid-20th century only strengthened this connection. For instance, see the 1953 Brach’s catalog below, where candy corn is listed as the first candy that “sell[s] in big volume throughout the Harvest season.”

This rise in candy corn’s Halloween popularity partly precipitated a problematic discovery: Candy corn was poisoning people. On Halloween night in 1950, children across the country fell ill with severe diarrhea and welting rashes. The FDA investigated what was going on and discovered the culprit: Orange Dye No. 1, a common food dye used in candies, including candy corn. According to a 1954 New York Times article, one piece of candy was 1,500 parts per million pure Orange 1. The dye was approved in 1906 (when food regulations first went into effect in the US), but nobody had reconsidered its health effects in fifty years. The reason the poisoning became evident on Halloween was because children consumed so much candy in one night (and, in turn, so much Orange 1) that they suffered major health effects that wouldn’t be so evident with smaller doses. In 1956, the FDA officially delisted Orange 1, and it hasn’t been used since.

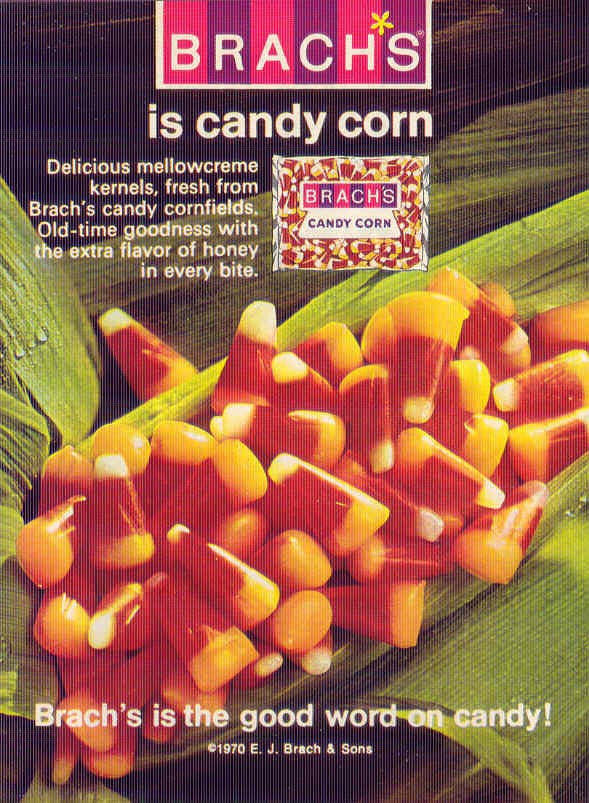

Candy corn tells a story of 20th century America. It is an agricultural relic, a product of mass marketing, a poison-free substance. I think this is all contained in Brach’s favorite candy corn marketing word: FRESH. “Fresh from Brach’s candy cornfields,” as one 1970 ad reads. Fresh like from a farm. Fresh like you just scooped it out of a penny candy bin. Fresh like free from deadly dyes. Fresh. Unless, of course, you let your bowl of candy corn sit out for too long…

Notes:

A good description of early candy corn production and distribution can be found here.

Many magazines and websites have published their own histories of candy corn, which provided useful information:

The Atlantic’s history of candy corn

Smithsonian Magazine’s history of candy corn

Vox’s history of candy corn

History.com’s history of candy cornA look at candy counters at Woolworth’s can be found here.

Some great 20th century candy corn ads can be found here and here.

More on the story of Orange 1 here.