We’re back! I took the winter off largely to work on a to-be-announced research project, which I’ll be sharing here as a multi-part history of technology story starting around Memorial Day, but until then, a few esoteric objects from the cabinet. First, some bugs…

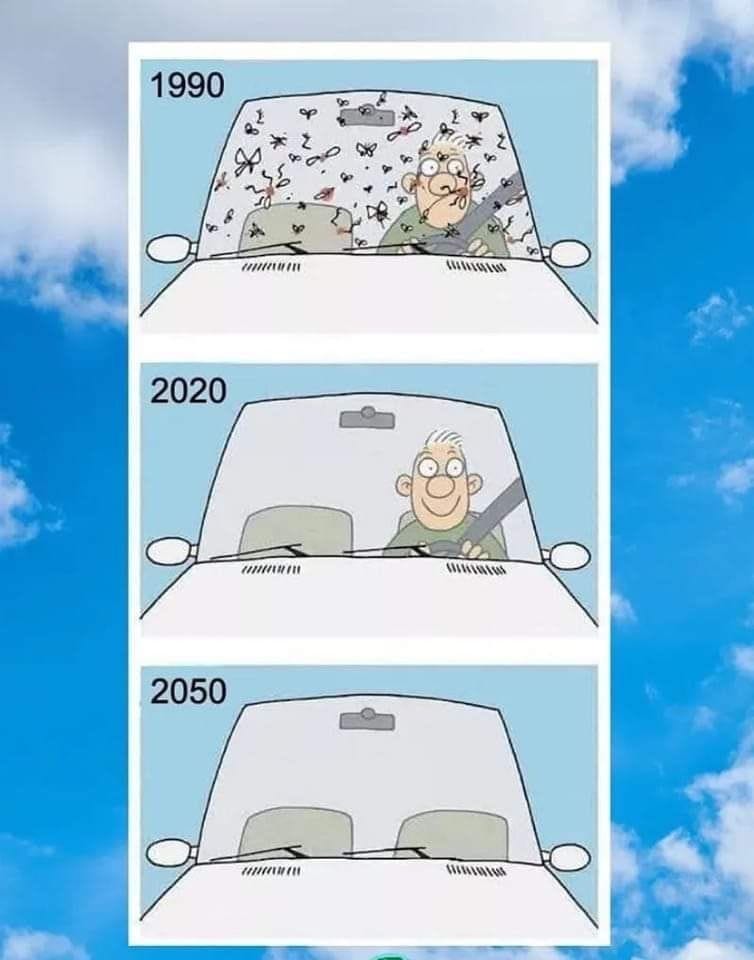

As a kid, I remember bugs splattering on the windshield of my parents’ car whenever we’d embark on long road trips. By the time we reached New York City from Portland, Maine, the car’s windshield would look something like the photo above. But, car trips I’ve taken more recently seem to end with perfectly clean windshields. I rarely feel the necessity to pull into a gas station and wipe my windshield clean with a squeegee.

This windshield phenomenon –– that fewer dead insects are accumulating on car windshields, especially since the early 2000s –– is well-documented. For instance, in 2004, the UK’s Royal Society for the Protection of Birds had 40,000 drivers attach a sticky film to their license plate; fifteen years later, in 2019, the Kent Wildlife Trust conducted a follow up study with the same methodology and found 50% fewer insect collisions compared to the 2004 data. Also in 2019, Dutch scientist Anders Møller published the results from a study that found the number of insects splattered on cars in the Netherlands declined by more than 80% between 1997 and 2017. Møller discovered that the decline in insect abundance predicted a decline in insect-eating birds. In other words, the windshield phenomenon is real, and it indicates something bigger and more concerning.

Around the globe, insects are going extinct. A study published in 2017, which tracked flying insects collected in nature preserves across Germany, found that in just 25 years the total biomass of these insects declined by 76%. A 2014 Science study found the mean decline in global invertebrate abundance to be around 45%. Over 40% of all insect species are currently threatened with extinction. “The decline is dramatic and depressing and it affects all kinds of insects, including butterflies, wild bees, and hoverflies,” said entomologist Martin Sorg, co-author of the 2017 study.

This is not good.

Insects matter. They often form the base of food chains, so when they disappear, so do other animals. They’re also often decomposers, helping to break down detritus and recycle nutrients in ecosystems. On top of that, plants –– including many of our crops –– depend on insects to pollinate. According to US Natural Resources Conservation Service, over a third of all food crops depend on pollinators to reproduce. Insects are important, and a loss of them is disruptive.

While the most apt descriptor of a cause for this loss might be the catch-all term “human impact,” according to a 2019 study, intensive agriculture is the biggest contributor to the insect declines. The Green Revolution (from World War II until the 1980s) industrialized agriculture practices, which increased crop yields and thus provided more food to people around the globe. However, the practices at the heart of the Green Revolution –– monocultures, artificial fertilizers and pesticides, modifying waterways, among others –– also led to major insect declines. The monocultures reduced insect food sources, pesticides killed insects and polluted habitats, and waterway modifications removed in-stream habitats for aquatic insects.

This is not over yet.

These trends in insect decline aren’t changing (if anything, they’re likely worsening), and they sit within the larger context of our contemporary mass extinction. Nearly every category of life on Earth is facing some degree of species loss right now. We talk about it often with the polar bears, but it’s just as true with bugs.

Just look at your windshield.

Notes and Further Reading.

While there is no simple solution to our current crises, my friend Johanna Wassermann –– who writes the lovely “Enthusiastic Environmentalist” newsletter –– provides a few action ideas here, including small steps like limiting your meat consumption or reusing more products.

Entomologist Manu Saunders wrote a critique of the windshield phenomenon as proof of an infection extinction here. I paint a one-sided picture above; read Manu’s writing for another side of the story. To quote a comment she wrote on her piece: “In the case of the windscreen phenomenon, there is no data to show this is true and a lot of reasons why it may not be a valid generalisation to prove global declines.” (I stand by the illustrative value of the phenomenon, but the lack of conclusive evidence is duly noted.)

You can read more about the windshield phenomenon in Mental Floss, The Telegraph, and The Guardian.

Yale published a good piece on why insects are disappearing. As did Science

This is not over yet.