In 1926, the Shedd Aquarium in Chicago wanted to ship live fish in a solid block of ice. It was a year before construction began on the aquarium itself, and associate director Walter Chute was figuring out how to get specimens to the forthcoming facility. The New York Times caught wind of Chute’s seemingly crazy plan and wrote a short blurb about it on June 8, 1926:

“The possibility of transporting Alaska blackfish to Chicago by freezing them into solid blocks of ice and then bringing them back to life by a thawing process is being investigated [for the] Shedd Aquarium. Early investigation has determined that the fish, the principal food of natives of Northern Alaska, have unusual vitality and are as lively as ever when thawed out after weeks in their icy prisons.”

On first glance, Chute’s idea seems ridiculous, but it’s grounded in some science. There are a handful of animals that can survive being frozen solid and then defrosted. For example, the wood frog –– which can be found across Canada and the Northeastern United States –– freezes solid every winter. The frog becomes motionless and has no detectable heartbeat or breath until spring comes, when it defrosts and resumes life in the marshlands. The frog can undergo this David Blaine like feat by, in essence, filling itself with antifreeze. Namely, as winter sets in, the frog produces both a special protein that removes water from the frog’s cells and glucose (sugar), which fills cells with a soupy liquid that doesn’t fully freeze in Canadian winter temperatures. The wood frog isn’t alone in this approach to winter survival: Animals from caterpillars to beetles all produce different antifreezes to survive deep freezes during dark winters.

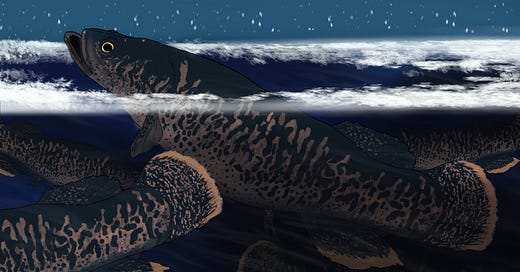

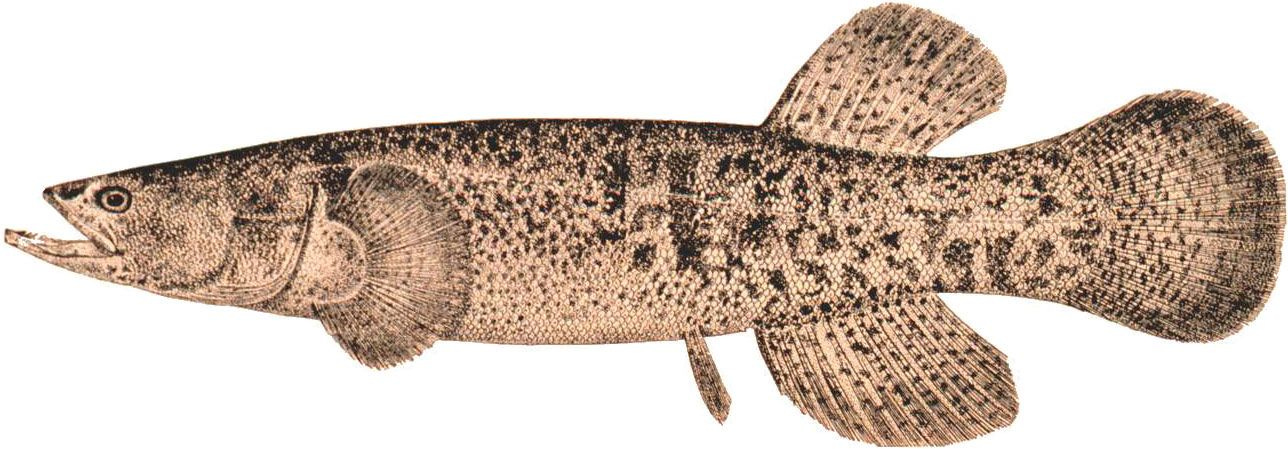

Blackfish, however, don’t take this antifreeze approach to winter survival. These small fish –– averaging around 4.5 inches in length –– are incredibly hardy. They remain active under ice in oxygen-poor lakes where other fish often can’t survive. They do so in part because of their ability to breathe oxygen straight out of the air; they’re the only arctic fish that can do so. The blackfish will find holes in the ice (often made by muskrats) and congregate at the surface to breathe before returning to deeper waters.

The Shedd’s interest in the fish, though, had little to do with the fish’s hardiness. Rather, the aquarium’s interest came from the fish’s cultural importance as a key source of sustenance for Native communities in Interior and Western Alaska. The blackfish, while small, has high nutritional value and is abundant in the winter, a time of year when food is often hard to come by. Because of this, in the Koyukon language, blackfish are known as oonyeeyh, which means “subsistence fish” or “the one you survive on.” In an interview for a US Fish and Wildlife research paper, a Native Alaskan said: “They say there is more vitamins in [blackfish] than any fish. … [If] there wasn’t that kind, there would be no people –– that’s what they survive on –– really important!” Another Native Alaskan interviewee said: “Boy they taste good! They taste the best. … They say there is vitamin A and D in there.”

So, Chute wanted to bring this important species to his new Chicago aquarium. But transporting them would be a challenge. In the early 20th century, when Chute was figuring out how to get blackfish from Alaska to Chicago, there was a perception that these fish could survive being frozen in a block of ice for weeks. This perception, first captured in writing in 1886 by American naturalist Lucien Turner, likely arose from the fish’s ability to survive in oxygen-poor environments.

Many Native Alaskans who have fed frozen blackfish to sled dogs have stories about the frozen fish coming back to life when defrosted. In the US Fish and Wildlife paper, one respondent said: “If you cook it for dogs, you throw it in the pot, and it starts swimming around again! They’re strong.” Another said: “They were getting it for dogs at Blackjack, in the lake. … Even if it freeze, then it turn alive again. Frozen, just like frogs, I guess.” This was the popular understanding of blackfish –– they could be frozen and defrosted, coming out no worse for wear. This dominant narrative likely inspired Chute to investigate freezing the fish for shipment.

Now, to spoil the punchline, we don’t actually know if Chute successfully transported blackfish in frozen blocks of ice. But it seems unlikely, despite the hopeful claims in the New York Times blurb.

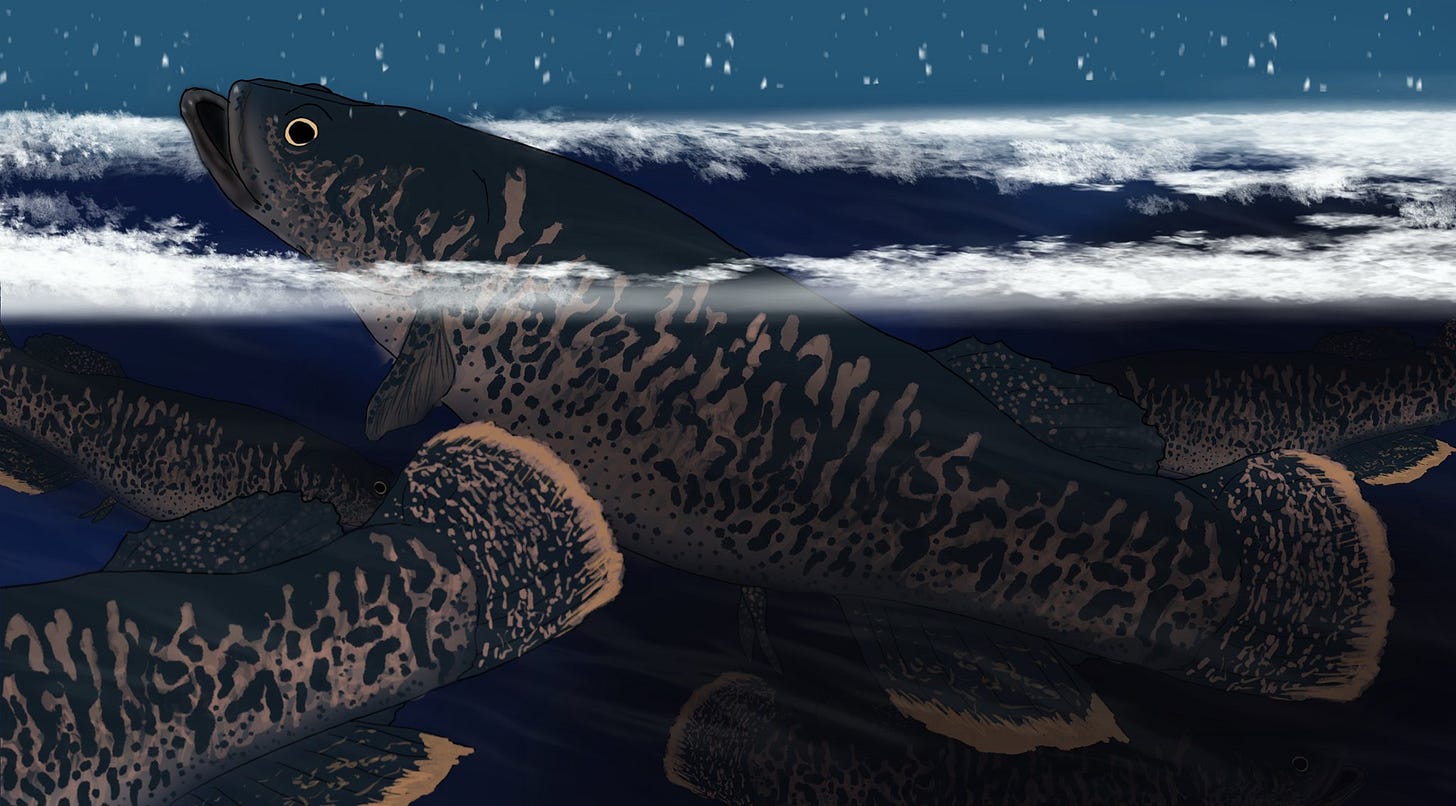

Physiologist Per Scholander was skeptical of the frozen blackfish legend. Two decades after that Times blurb, in 1948, Scholander traveled to Barrow, Alaska with scientist Laurence Irving to study how plants and animals survive extreme cold. The last chapter of the book they co-authored was dedicated to “Experiments on Freezing the Blackfish.”

In their first experiment, Scholander and Irving captured eight blackfish and frozen them in a block of ice. When thawed, all the fish were dead.

In a second experiment, two fish were dipped in antifreeze chilled to subzero temperatures. The fish, frozen from their pectoral fins to their tails, thawed and survived for five days before dying. However, even during these brief second life, blood circulation never returned to the frozen parts of the body, and the fish swam using only their unfrozen fins. Scholander and Irving wrote that “the blackfish, like man and other animals, can survive being partially frozen,” which seems like an overly optimistic spin on the outcome of this experiment.

In a final trial, the team froze the heads of five blackfish. After thawing, the fish –– this time with working bodies but dead heads –– swam around for a day before, once again, dying.

Therefore, Scholander and Irving concluded that blackfish cannot survive a deep freeze. They aren’t wood frogs. The scientists do note, though, that “indeed a fortunate observer may still see the dogs throw up the fish alive, provided only that the fish were not too hard frozen.”

“Not too hard frozen,” however, was not Chute’s plan. Thus, even though the Times claims initial attempts were successful, in light of Scholander and Irving’s later experiments, it seems unlikely that Chute managed to freeze and ship blackfish from Alaska to Chicago. Somehow though, the fish did arrive safely at the Shedd. In 1930, when the building opened, the Shedd was the first aquarium to use a large scale water chiller, which allowed the aquarium to display Arctic rarities such as the blackfish. It was the first time Alaska blackfish were displayed at an aquarium.

But how they got to the Shedd is still, if you will, a cold case.

Notes.

As one does on a weekend, I was looking through the New York Times archive for 1920s articles on ice cream when I stumbled upon the 1926 New York Times blurb. I was hooked and hence this post.

The wood frogs information is pulled from this National Park Service article.

The quotes from Native Alaskans on blackfish come from this report, published by the US Fish and Wildlife Service in 2004. More info on blackfish pulled from the US Fish and Wildlife Service here.

Ned Rozell wrote a wonderful article on the Scholander experiments here.

Some additional information about the Shedd and blackfish is from “Drum and Croaker,” volume 52 (Feb 2021).

The Shedd also spent $3,000,000 to try and keep an octopus alive!? A story for another day…