Steven Thaler’s “A Recent Entrance to Paradise” feels like the sort of art you might find in a hotel room or a doctor’s office. It’s innocuous and rather boring – except for the fact that it has been at the center of a prolonged copyright dispute.

The work was created, in Thaler’s words, “autonomously … by a computer algorithm running on a machine.” In other words, the work was made by AI, and Thaler wanted the AI algorithm (not himself) to hold the work’s copyright.

But the Copyright Office wasn’t having it: Twice, they rejected his claim on the basis that copyrights are only granted to works with “human authorship.”

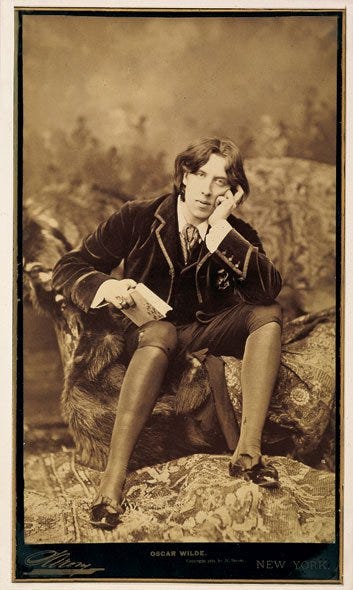

This question of “human authorship” for works of art isn’t new. For instance, consider an 1884 court case around copyrighting a photograph. In the case, photographer Napoleon Sarony filed a suit against the Burrow-Giles Lithographic Company because Burrow-Giles sold unauthorized prints of Sarony’s photograph of Oscar Wilde. The company argued that a photograph is not “human-authored” because it is a mechanical reproduction of the “exact features” of some natural object or person.

However, the court rejected this argument. They noted that photographs require some degree of human involvement; they are “representatives of original intellectual conceptions of [an] author.” The court said that by posing Oscar Wilde in front of the camera and selecting his outfit and backdrop, Sarony “produced the picture in suit.” This control over subject allowed Sarony to be the author of his photograph. (It’s interesting, though, that the court didn’t cite Sarony’s framing of his subject, which raises the question of how this ruling would’ve been different if its subject weren’t posed – e.g., a photo of a mountain. But I digress.)

In the 1970s, the Copyright Office realized that the introduction of computers was going to further challenge this idea of “human authorship.” So, they assembled the National Commission on New Technological Uses of Copyrighted Works to address the relationship between new computing technologies and copyright. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the Commission concluded that, once again, even if a computer was used to make something, “the presence of at least minimal human creative effort” was necessary for a copyright claim. In essence, they reinforced the ruling of the Sarony case in a digital age.

Of course, in Thaler’s case, it’s easy to see that the algorithm was designed by a human, so there is “at least minimal human creative effort” involved. However, Thaler isn’t trying to copyright the art for himself. He’s trying to copyright “Paradise” on behalf of the algorithm. Yes, he wants a computer program to hold the copyright. And that’s where the Copyright Office drew the line; placing a copyright with a supposedly-autonomous machine would violate the “human authorship” tenet of copyright law. The Copyright Office saw the algorithm as an extension of Thaler, not something distinct from him.

However, in September 2021, Thaler brought a similar case forward in Australia where – in a world first – a judge of the Federal Court of Australia ruled that AI is capable of being an “inventor.” The opposite of the US ruling. The judge noted that, according to Australian law, there was “no specific provision” that prohibited AI from being an inventor. Thus, at least in Australia, the algorithm could (potentially) hold the patent…

The line between human and machine continues to blur.